Planning for dementia

The number of Irish people with dementia will almost triple over the next 30 years. eolas considers the reasons for the increase and the need for a strategy to tackle the condition.

The number of Irish people with dementia will almost triple over the next 30 years. eolas considers the reasons for the increase and the need for a strategy to tackle the condition.

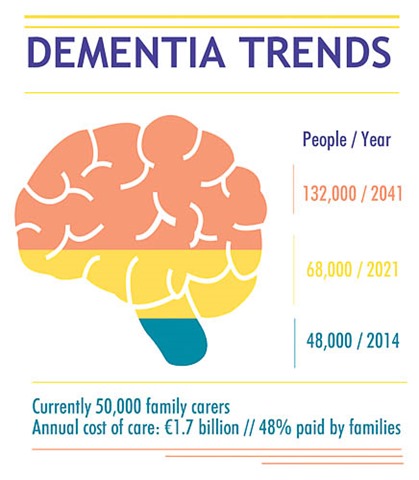

Every day in the State, around 48,000 people are experiencing a slow deterioration in how they think and relate to those around them due to dementia. The number is expected to rise to 132,000 by 2041.

Most live at home (63 per cent) and this group is supported by 50,000 close relatives. The estimated cost of dementia care is €1.7 billion per annum with half of that borne by families.

Ireland has the EU’s youngest population and the incidence of dementia will therefore grow as our age structure grows older.

The Programme for Government pledged that a dementia strategy would be produced by 2013. A public consultation took place in 2012. Late last year, Minister for Primary and Social Care Kathleen Lynch stated that the strategy had been postponed until the first quarter of 2014. Before the summer recess, she commented that it was “at an advanced stage of preparation.”

This delay means that Irish policy has fallen behind the UK in tackling the condition. A national dementia strategy for England was published in 2009 and followed up by similar versions in Scotland and Wales.

Northern Ireland’s strategy was launched in November 2011 and emphasised the need for early diagnosis, a better public and professional understanding of the condition, and a staged approach to care which helped people to live at home as long as possible.

Lobbying

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia followed by vascular dementia (caused mainly by strokes). In its response to the Department of Health’s consultation, the Alzheimer Society of Ireland called for a specific clinical directorate to deal with dementia, oversee the strategy and ensure that other parts of the Health Service are aware of the condition and its consequences. Indeed, this is seen as a ‘whole of government’ issue as several public services are needed to support those affected.

People with dementia and their carers must be involved in the decisions that affect their lives and recognised as the experts in the “lived experience” of the condition.

The society also wants dementia to be seen as a social issue which needs a community response. The focus here should be on the person’s abilities and their possibilities in life. A system of well-managed ‘care pathways’ should ensure better co-ordination between carers and health professionals. A world class research base is also sought, including an accurate baseline for the prevalence of dementia which will help Ireland to plan for the future.

Seven priorities were set out:

1. getting a diagnosis, disclosure and early intervention;

2. helping the person to live well in the community;

3. improved care in the acute hospital setting;

4. a better quality of life in residential care;

5. palliative and end-of-life care;

6. supporting people with younger onset dementia; and

7. tackling stigma and raising awareness.

The Institute of Public Health in Ireland, meanwhile, outlined the main risk factors which determine whether a person may develop dementia.

It is true that the risk increases with age but also that the needs of younger people with dementia are “far more complex” than those of older people. Men have a higher prevalence up to the age of 75 but it is much more common in women after that point – this reflects the longer female life expectancy.

People with Down’s syndrome have high rates of dementia and the condition affects one in 550 people born in Ireland, compared to one in 1,000 in Britain. These people tend to be among the younger sufferers as they have a life expectancy of 50-60 years. Some rare forms of dementia are inherited.

While the above factors cannot be modified, a person can reduce their risk by maintaining a healthy diet and low blood pressure, and reducing or avoiding smoking and heavy alcohol consumption. High levels of physical and mental activity – and strong social networks – can also help.

While the above factors cannot be modified, a person can reduce their risk by maintaining a healthy diet and low blood pressure, and reducing or avoiding smoking and heavy alcohol consumption. High levels of physical and mental activity – and strong social networks – can also help.

A Department of Health spokeswoman told eolas that the strategy was delayed because more work was needed to make it cost-neutral. It is now due to be published by November.

In the meantime, Atlantic Philanthropies has provided €14.7 million in grants to improve the care and well-being of people living with dementia. Minister Lynch welcomed the investment as “one of the most important” in recent years and explained that the funding will help to implement the national dementia strategy.

A research programme will also be funded in conjunction with the Health Research Board and supported by €1 million in match funding from the Department of Health.

The Health Service Executive will meanwhile provide €15 million in match funding for intensive home care support, GP education and training, and dementia awareness.

The announcement was welcomed by the Alzheimer Society of Ireland. Chief Executive Gerry Martin said: “Ring-fenced funding for dementia is long-awaited and much needed, as we are working from a severe deficit in relation to investment and services for people with dementia in this country.” He added that the society looked forward to the “overdue publication” of the strategy.

Life with dementia

Insightful quotes from carers and those cared for were included in the Alzheimer Society’s submission.

“What I do now is walk around with a smile on my face because I’m still alive and I’m still happy, enjoying my life,” said one person after their diagnosis. Another admitted: “It is hard at times because of the things you can no longer do. You definitely feel different.”

One carer emphasised the need to integrate people with dementia into society “rather than keeping them on the periphery.” A family with a younger person with dementia found that “having a diagnosis under 65 means you don’t fit into any box in the Health Service” as it wasn’t considered a disability.