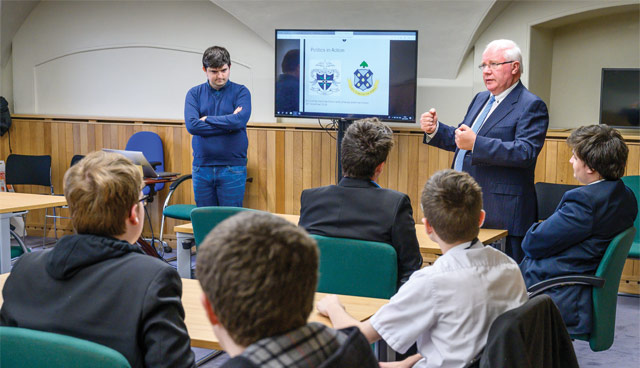

Politics in action

Students from St Columb’s College, Derry and Limavady Grammar School came together as part of the Politics in Action programme, a cross-community, cross-border initiative to acquaint them with the mechanisms of government in Belfast, Dublin and London. Odrán Waldron reports from their visit to Leinster House.

The students may have gotten an even better initiation into Dublin politics than they had bargained for when they found their entrance into Leinster House delayed by 30 minutes due to the traffic backlog caused by a farmers’ protest against beef prices, where tractors were driven into Dublin City centre and as close to the Dáil as Gardaí would allow.

While schools from Belfast, Newry, Bessbrook, Newtownhamilton and Crossmaglen all also participated in the Politics in Action programme, the visit of the two schools from Northern Ireland’s north west to Dublin bore special significance given their proximity to the border between Derry and Donegal. St Columb’s, situated in the Derry suburbs on the Buncrana Road, is less than five minutes, roughly three kilometres of a straight road, to County Donegal; Limavady Grammar being roughly 30 minutes, or 18km, away on the A2 road.

Given their border constituency status, it was perhaps fitting that their first speaker of the day was a representative of a border constituency in his own right. Fianna Fáil’s Brendan Smith, TD for Cavan-Monaghan since 1992 and parliamentary party chairman, as well as Chair of the Joint Committee on Foreign Affairs and Trade and previous holder of four separate ministerial positions was the first to speak to the students.

He explained his everyday work as a parliamentarian and the work undertaken to represent his constituents, which naturally now extends to discussions around Brexit, a topic that hung in the air throughout the day. Smith said that the decision of the UK electorate to vote to leave the European Union “was one with profound implications that I was absolutely opposed to” and that “our political system has been consumed by Brexit”.

The long-serving TD spoke of visiting delegations from other EU member states and accompanying them to border areas in order to show them “the reality of the interdependence of our economies”. He also recalled the days before the Good Friday Agreement, long before these students’ births, and having to navigate security and customs checkpoints while campaigning due to the roads of Cavan and Monaghan intersecting with Fermanagh so frequently.

Before moving on to the questions and answers section, Smith lamented the fact that the North South Ministerial Council, which he has participated in, can no longer meet, calling its absence a “huge deficiency in what was happening in terms of north/south co-operation”.

When asked in the Q&A if he feared for the future of north/south relations, Smith said: “I don’t fear for the future, but we could be strengthening them. We’re too small a country not to be collaborating.”

When asked forthrightly if he desired a united Ireland, Smith answered: “I’m a person that wants to see a united Ireland but through the mechanism of the Good Friday Agreement. All-Ireland bodies are working well. We should work the institutions.”

Following Smith was the Labour Senator Aodhán Ó Riordáin. Ó Riordáin began proceedings by regaling the students with his political history, beginning with his awakening as primary school teacher in Sheriff Street in Dublin’s inner city, where he was the first male teacher in 150 years.

Exposed to the poverty of Dublin’s north inner city for the first time, Ó Riordáin went on to become a Labour Party Dublin City Councillor in 2004, a TD in 2011 and after losing his seat in 2016, a member of Seanad Éireann. Ó Riordáin, of course, discussed Brexit with the students, saying that victory for the leave side of the vote had been the “classic example of what happens when you’re not watching”.

“Brexit was the result of a 30-year propaganda war by sections of the Conservative Party against the European Union,” he told the students. “The Good Friday Agreement has been ripped up and thrown in the bin by the Brexit process.”

Ó Riordáin also spoke of his work in the areas of drug law reform and the protection of employment rights, two areas particularly relevant for the Derry City and Strabane constituency, which has Northern Ireland’s lowest employment rate, 61.6 per cent and highest economic inactivity rate, 34.1 per cent. After referencing recent heroin-related deaths in Belfast, he called the UK’s drug policy “really regressive” and note that Ireland has the third highest overdoes rate in Europe. He detailed the struggles to secure planning permission for a safe injection centre in Dublin and said that that there was “massive inequality” placed on the value of certain lives in both Ireland and the UK.

Speaking to a Catholic boys grammar and non-denominational co-educational selective grammar, Ó Riordáin stressed the importance of shared education and placed the blame for the lack of shared education in the Republic of Ireland, where one third of secondary schools are separated based on gender, at the door of the Catholic Church. During the Q&A section that followed his talk, he claimed that the “Catholic Church has had far too much influence in Ireland” and decried the fact that the Department of Education “doesn’t have a hands-on role in education”. “I would like to have a change in the Irish Constitution to get religion out of schools,” he told the students, saying that a referendum was necessary as the Church would never willingly give up their “vice grip on the education system”.

In another robust and forthright Q&A session from the assured and engaged students, Ó Riordáin was asked who he blamed more for Labour’s downturn in electoral fortunes, former leader Eamon Gilmore or his now-deposed successor Joan Burton. Neither, he answered: “The easiest thing in the world to do is to not go into government.”

When asked about the impending climate crisis that will ignore any borders, Ó Riordáin, a former Labour spokesperson for the environment, said that “hard questions need to be asked of people”. “People have to be discommoded,” he told the students. “The farming community needs to be brought on board. They’re quite a powerful lobby group who can make or break a politician’s career. Nothing can ever be the same again and we can’t pretend that things can be the same because the stakes are far too high.”

Following the meeting with Ó Riordáin, the students were treated to lunch in the Leinster House canteen before watching Leader’s Questions and then going on a tour of the Houses of the Oireachtas.

“We thought, in terms of cross-community work that this was very important,” St. Columb’s teacher William Boyle said afterwards. “I know our school is very keen on getting people from all across the divide to work together.” Melanie Cartwright of Limavady Grammar agreed: “We also wanted to give our Politics A Level students this experience with students from a different background so that they might understand the challenges of working in politics.

“It’s really important for children from border communities in the north west to engage with the southern political system,” said Cartwright. “Whatever shade of political opinion you have, the decisions made in Dublin will impact our lives in the north west, the same as decisions made in Stormont will impact lives in Dublin. The experience of bringing students to this institution, along with Belfast and Westminster, makes the institutions that we study in class a lot more tangible not just in their academic settings but as they become first-time voters in the next few years.”

“The experience of bringing students to this institution, along with Belfast and Westminster, makes the institutions that we study in class a lot more tangible not just in their academic settings but as they become first-time voters in the next few years.”

This sentiment was echoed by Boyle: “It’s getting them different perspectives constantly and seeing what the powerbrokers do and work at. Seeing what people actually do and how it affects them in the long terms is what this does for them.”

On Brexit, the teachers said that they had seen a change in attitude amongst students following the result of the 2016 referendum. “I think it has gripped them more and they want to ask more questions about why Stormont isn’t up and running,” Cartwright said. “It’s the impatience in the youth, particularly because the north west feels like we play second fiddle to county Antrim. There is that impatience of asking ‘why not us?’

“Last week we were talking about Brexit and the opportunity of studying in the north west, but so many of the young people, and my generation before them, felt that you had to go to Belfast if you wanted to stay in Northern Ireland.”

Boyle agreed with that contention, concluding: “Brexit is really acting as a shining light to those other issues. It has been a catalyst for young people getting involved actively. There’s been a huge increase in the number of first-time voters within the UK. The knock-on effect has to be a good thing.”