Pre-Budget 2023: An economic snapshot

Budget 2023 will deliver an overall package of €6.7 billion and a 6.5 per cent increase in core spending as the Irish economy continues to grow, driven largely by the strong performance of the export sector. However, significant challenges lie ahead, with inflationary pressures, tight labour markets, and rising interest rates all having an impact.

Budget 2023 will deliver an overall package of €6.7 billion – €5.65 billion of additional public spending and €1.05 billion of taxation measures – with a “focus on cost of living”, the Government announced in Summer Economic Statement 2022. Within the statement, the Government pledged to increase core spending by 6.5 per cent in 2023 as figures show an Exchequer surplus of €4.2 billion for the first six months of 2022 and a €2.1 billion surplus on a rolling 12-month basis ending June 2022. A 3.5 per cent decrease of €1.4 billion was recorded in total gross voted expenditure for the first half of 2022, leaving the half-year total at €38.5 billion.

While the pledged increase in spending will more than account for the surplus of the last year, the Government still considers the possibility of running a “very modest” surplus in 2022 and 2023 possible though highly uncertain due to its reliance on corporation tax receipts. Such tax receipts drove strong growth in Exchequer tax revenues to end-June 2022, which stood at €36.9 billion, a 25 per cent increase that is caveated by the stringent lockdown measures in place during the same period in 2021.

Growth slowdown

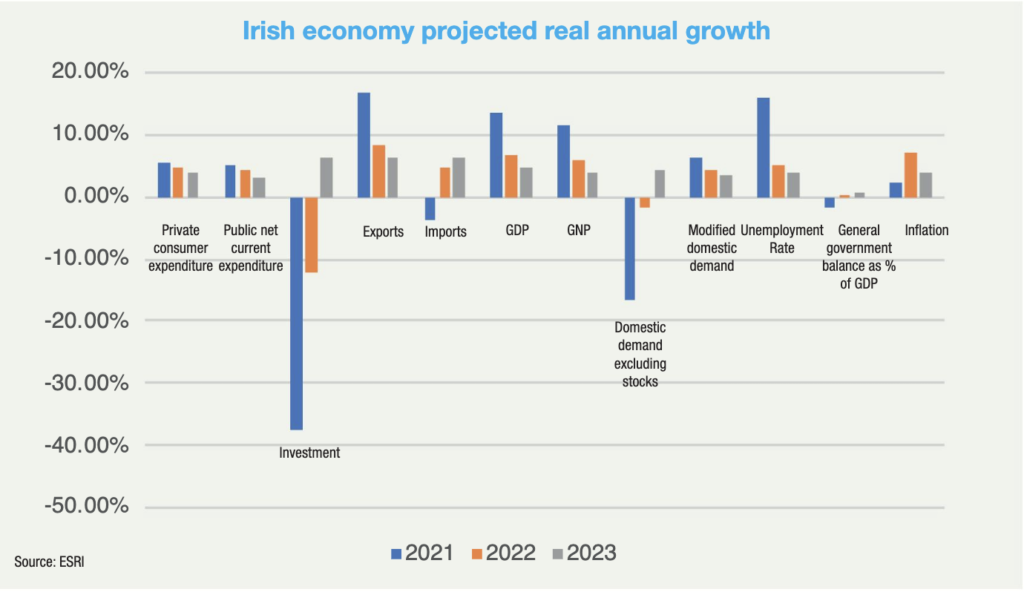

The Irish economy is predicted to continue its growth, although this is set to be at a slower rate than previously forecast. The Economic and Social Research Institute’s (ESRI) Quarterly Economic Commentary for the end of Q2 2022, revised its prediction for the growth of modified domestic demand (MDD); having predicted a growth of 5 per cent in 2022 and 4.5 per cent in 2023, the projected growth in MDD is now set at 4.4 per cent for 2022 and 3.7 for 2023. GDP is expected to grow by 6.8 per cent in 2022 according to the ESRI and by 4.8 per cent according to the OECD.

Overall, however, this would represent a significant slowing in the pace of growth, from a 13.5 per cent rise in GDP in 2021, and while the ESRI projects inflation to stabilise in 2023 and average at 4 per cent for the year, it predicts a further fall in GDP growth to 4.8 per cent for next year. The OECD, in its June 2022 Economic Forecast Summary, predicts a slowing to 2.7 per cent growth.

Such revisions in the forecasts reflect the constrictive impact of inflationary pressures currently being experienced globally, with the economic commentary forecasting that inflation will average 7.1 per cent in Ireland for the year 2022 in light of the war in Ukraine and the disruption of food and energy markets.

There is also, however, the precedent set by states who routinely run budgetary surpluses, such as the Netherlands, Germany, and Japan, often criticised by notable economists such as Thomas Piketty, whereby profits are retained, meaning that they are not divested into the economy through increased wages to the work force. This results in weak private consumption demand and a slackening of growth.

With the European Central Bank (ECB) signalling that monetary policy rates will increase in the coming yearly quarters, the ESRI predicts that this will dampen investment sentiment and consumer spending, perhaps most notably in a predicted 2 per cent fall in Irish house prices relative to where they would have otherwise been expected to be, although it is noted that lack of supply will continue to exert upward pressure on these prices.

Exports and imports

Fuelling the strong if simultaneously slackening performance of the Irish economy is the export sector, with Irish net exports standing at €53.3 billion in Q1 2022, having grown by 5.2 per cent on a quarterly, seasonally adjusted basis, and increasing by 14.4 per cent year-on-year. Goods exports grew in Q1 2022 on an annual basis across all major groupings, with the chemicals and related products group recording the largest growth rate, 61.8 per cent.

Service exports also increased significantly; computer services, which account for almost 60 per cent of total service exports, grew by 24.7 per cent on an annual basis, although they did decrease by 8.5 per cent from Q4 2021. While business services exports grew on both an annual and quarterly basis, exports of financial services fell after a successful 2021, declining by 4.9 per cent on a quarterly basis and 9.3 per cent annually.

Inflation and the cost of living

Global food prices rose by nearly 30 per cent in 2021 amidst a two-year surge that has only been exacerbated by the Russian ongoing invasion of Ukraine; the World Bank’s Food Commodity Price Index reached a record high in nominal terms during March/April 2022 and showed a 15 per cent increase over two months, along with an increase of over 80 per cent over two months.

Similarly, the already-rising costs of energy were worsened by the Russian invasion, leaving Ireland exposed. As a member of the European Union, the State is vulnerable to any jeopardisation of Russian fuel supplies, although the Corrib gas field and interconnection with Britain mean that this is reliance is not as great as the reliance in central and eastern Europe. That being said, with 70 per cent of natural gas – which accounts for around 35 per cent of Ireland’s energy requirements – imported from Britain, the island is severely exposed to the British Government’s energy policy decisions in winter 2022/2023.

Overall, the ESRI projects that domestic inflation will average 7.1 per cent for 2022 and 4 per cent for 2023 but warns that if “global pressures contributing to price increases were to intensify, this is likely to pass through to domestic inflation in a sustained manner”.

Inflation in the eurozone stood at 8.9 per cent in July 2022, representing an all-time high. Despite this inflation largely being a result of the surges in energy and food costs, the ESRI notes that increases are “being observed more broadly in the economy”. In an attempt to tackle inflation, the ECB has announced that it will end its Asset Purchase Programme and likely increase the policy rate from

-0.5 per cent, by a minimum of 50 basis points. Rising interest rates will likely see an increase in the servicing costs of debt domestically, along with a lower credit demand, which may, the ESRI says, “offset some of the recent demand-side pressures, in particular in the housing market”.

The labour market and private consumption demand

May 2022 marked the first month in which the unemployment rate (4.7 per cent) fell below February 2020’s pre-pandemic rate of 4.8 per cent and the ESRI predicts that the economy is “likely to be operating to or at full employment over the coming period”, with unemployment forecast to fall as low as 4.2 per cent by Q4 2022.

The labour market showed strength with employment growth in high-wage and high-tech sectors, but the annual average wage growth forecasts of 3.5 per cent in 2022 and 4.5 per cent in 2023 do not keep pace with inflation rates, meaning that wage rates are set to decline on a real basis.

One metric that suggests that wages could increase further is a notable vacancy rate in the labour market, with an 80 per cent increase in vacancies from Q4 2019 to Q1 2022, an overall increase to 32,900 vacancies from 18,100 across all sectors. With these vacancies typically concentrated in high-wage, high-skill sectors, wages are forecast to continue to rise through 2023 and while this will lead to hopes that take-home pay could keep pace with inflation, it will also lead to fears of a wage-price spiral.

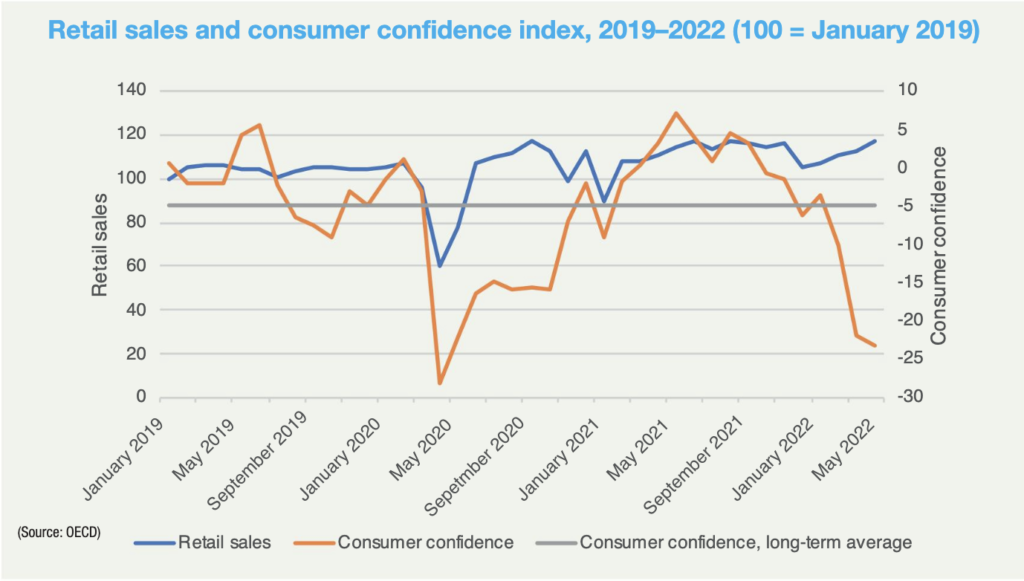

A fall in wages in real terms will inevitably impact private consumption demand, which in turn will limit the growth of the domestic economy. The ESRI predicts private consumer expenditure for 2023 to continue to grow, but for that growth rate to slow to 3.8 per cent in comparison with the 2022 forecast of 4.6 per cent. Meanwhile, the OECD has noted a “marked deterioration in consumer sentiment” due to “steadily rising consumer prices, combined with uncertainties around the war in Ukraine”, which have “fuelled uncertainty”.

Having recovered from the worst of the Covid pandemic and recorded growth rates between 5.9 per cent and 16.2 per cent in the four quarters of 2022, MDD is now forecast to have its growth rate slowed down to 3.3 per cent on an annual basis for Q2 2022. Due to the upward pressure in inflation and downward revision in its consumption forecast, the ESRI now predicts the growth rate to decline for the remainder of 2022 and average 4.4 per cent in 2022 relative to 2021.

Budgetary actions

It is expected that Budget 2023 will include the introduction of a new tax bracket, with two options – 30 per cent rates for those earning €36,800-€41,800, costing the Exchequer €525 million a year, or for those earning between €36,800 and €46,800, which would cost €945 million per year – estimated to save taxpayers between €500-€1,000 per year per person. Boosts to social and child welfare payments are also said to be being mooted, but, as with tax breaks, it is difficult to see how these boosts in take-home pay would not be immediately swallowed by an inflating market unless their rates are tagged to inflation. Simultaneously, it is important to consider that Ireland’s surplus, large enough to handle the cost of these new tax brackets, is largely dependent upon the receipts of the notoriously volatile corporation tax and taking such money from the Exchequer requires a stability of income elsewhere.

The OECD states that measures such as untargeted electricity credits have thus far provided “only limited protections to poorer households” and suggests that future supports should “focus on temporary assistance to the most vulnerable and productivity-enhancing public investment”. Despite wage growth, it predicts that “high inflation will cut real household disposable income and weigh on firms’ investment decisions, especially in 2023, as the embargo on Russian oil takes effect” as of 5 February 2023.

To protect against this, the Government pledged a 6.5 per cent increase in public spending, which will exceed its previously pledged limit of 5 per cent rises from 2023 to 2025. With that increase totalling €6.7 billion, attention will now turn to how the Government distributes that increase and how it mitigates the coming pressures of global inflation.

Having pledged to put more take-home pay in the pockets of citizens, it remains to be seen how effective the Government’s approach will be amidst rising costs, but with the projected wage loss in real terms, it appears unlikely that this will be the last Budget defined by cost of living in the coalition’s mandated tenure.