Micheál Martin TD’s return as Taoiseach has seen Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael get an exclusive share of the spoils at Cabinet level, while the new Programme for Government (PfG) sets the tone for a diluting of the liberal policies – including on social welfare and the environment – pursued under the previous administration.

The 2025 Programme for Government (PfG), Securing Ireland’s Future, presents a vision of economic stability, infrastructural development, and administrative efficiency. While it addresses longstanding challenges, the broad proposals prioritise continuity over the kind of radical reform proposed in the 2020 Programme for Government, Our Shared Future, with a measured approach to housing, economic growth, social welfare, and climate policy.

Whereas in 2020, there were bold new ambitions announced on retrofitting, energy, the environment, and housing, the 2025 PfG reinforces government’s commitment to a “competitive, open market economy”. The focus is on fiscal responsibility, reducing “regulatory burdens”, and supporting enterprise growth. A National Competitiveness and Productivity Action Plan is promised within 12 months, covering industrial policy, infrastructure investment, digital regulation, and trade expansion.

Job creation remains a key pillar, with a target of 300,000 new jobs by 2030. However, unlike previous strategies, this plan offers limited sectoral breakdowns beyond general references to high-tech, financial services, and agri-food.

The commitment to research and development is emphasised, with an expansion of Enterprise Ireland’s funding for start-ups and scale-ups, alongside enhanced tax credits for innovation.

Housing

Housing remains central to government policy, with the previous government’s blunder in its vastly overstated projection for housing delivery prior to the general election having reduced confidence in the sector.

In the PfG, the focus is now on increasing supply rather than interventionist affordability measures which were so prominent in Housing for All. The PfG states that the Land Development Agency will play a pivotal role, with state-owned land being utilised for housing projects, though the specific number of units is undefined in the document.

Shared equity schemes and first-time buyer supports continue to be the preferred instruments for affordability, despite multiple critiques hinging on the potentially inflationary impacts. Other proposals with significant support within the sector, such as rent control measures, are absent, replaced with a commitment to reviewing tenancy laws for “long-term stability”. Public-private partnerships are expected to expand in social and affordable housing projects.

Similarly, a commitment to hold a referendum “on housing” present in the 2020 PfG has been quietly dropped.

Social protection and justice

Social protection measures in the 2025 PfG focus on refining existing schemes rather than introducing new universal benefits. Welfare supports will undergo a “targeted review,” with an emphasis on efficiency rather than expansion. Commitments to disability support highlight “a step change” in services but lack concrete proposals beyond increasing access to employment.

The Department of Justice is to be re-named to the Department of Justice, Home Affairs and Migration. This is reflected in the PfG, which states that migration policy will have a “fair but firmer” stance, indicating a streamlined asylum process with an emphasis on faster decision-making and removals.

Direct provision – which the previous government promised it would abolish – remains under review, with no firm commitments to alternative models beyond “enhanced reception services”. Although the new Minister, Jim O’Callaghan TD has set out his stall with a more right-wing tone than his predecessor. “If you come in and you refuse international protection, you leave. You’re gone,” O’Callaghan told reporters on 13 February 2025.

Climate and energy

The Government reiterates its commitment to decarbonisation but with a focus on balancing economic competitiveness. The offshore wind sector is a listed priority, with regulatory frameworks being adjusted to accelerate development. However, there is less emphasis on direct public investment, with private sector-led solutions preferred.

‘Energy’ is not explicitly referred to in the PfG’s contents page. In fact, the first mention of note is on page 52 under the ‘leading a revolution in renewable energy’ subhead. There are two mentions of ‘renewable green’ or ‘green hydrogen’, alongside two vague references to ‘energy security’.

Retrofitting programmes are set to continue, but with a shift towards incentivising private investment rather than large-scale state grants. The target for phasing out fossil fuel vehicles remains but includes “flexibility for emerging technologies,” potentially softening the 2030 ban on new petrol and diesel cars, although EU legislation will require the sale of petrol and diesel cars to be banned from 2035.

|

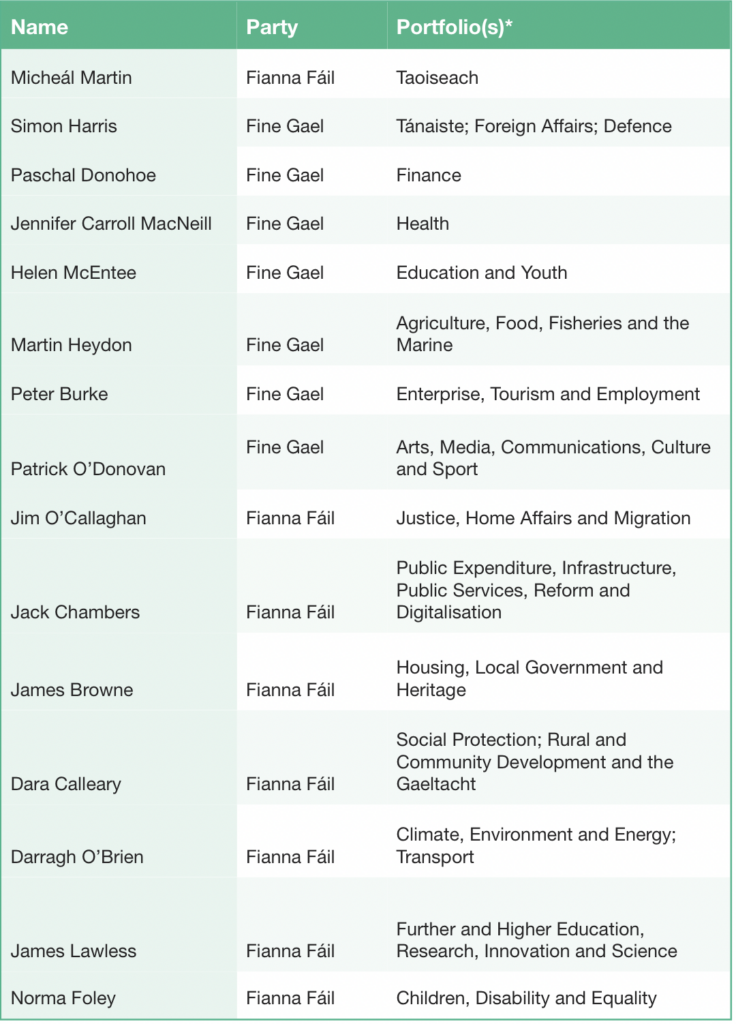

35th Government of Ireland: The Cabinet There are 15 members of the new cabinet, collectively controlling 18 government departments (The position of Tánaiste formally falls within the remit of the Department of the Taoiseach). Tánaiste Simon Harris has two portfolios (Defence and Foreign Affairs), as does Darragh O’Brien (Climate, Environment and Energy; and Transport), and Dara Calleary (Social Protection; and Rural and Community Development and the Gaeltacht). Three of the 15 Cabinet ministers are women, while the parties have granted 10 of the 18 portfolios to Fianna Fáil, and eight to Fine Gael. 11 of the 15 members are from Leinster, while three (including the Taoiseach) are from Munster, one comes from Connacht, and none are from Ulster. Overall, the new cabinet has less diversity than the previous one by gender, geography, party, and religious background (owing to Heather Humphries’ departure from politics). |

|

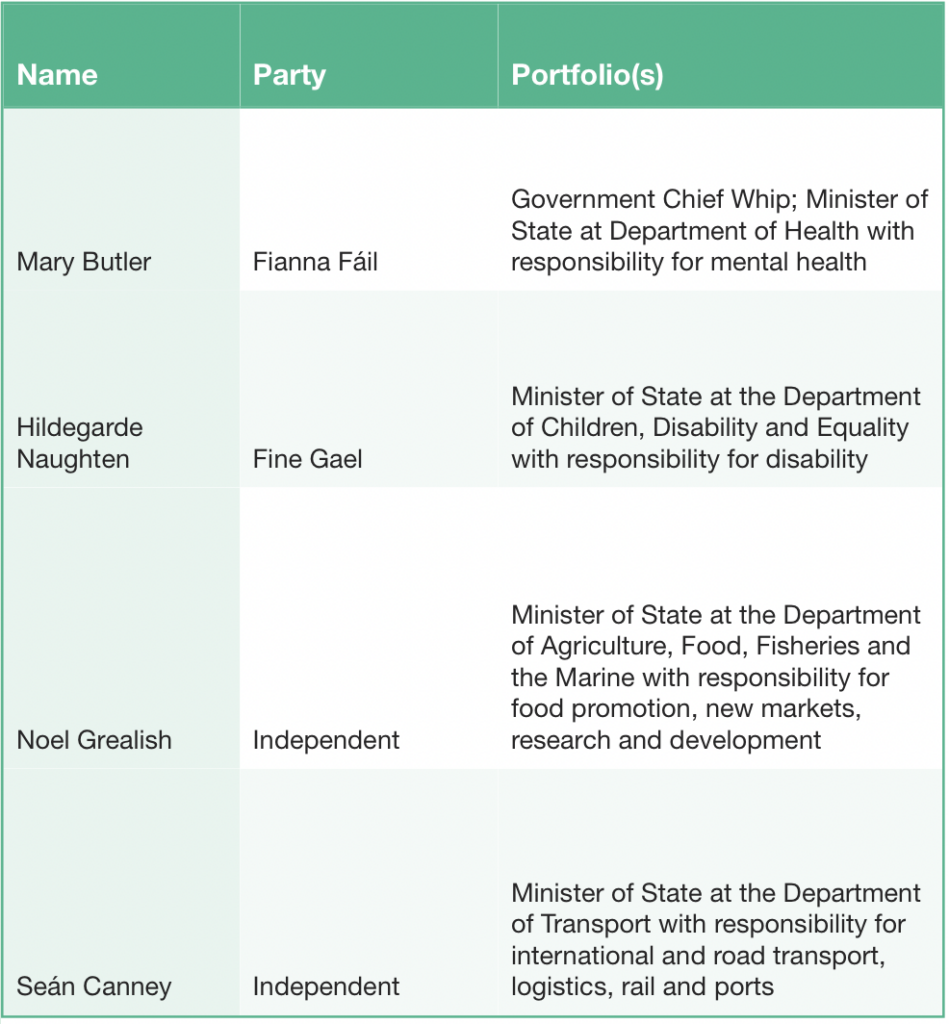

Ministers of State attending Cabinet Four ministers of state (known as junior ministers) will also attend cabinet meetings. Ministers of state who attend cabinet are known as ‘super junior ministers’. The job of Government Chief Whip rotates back to Fianna Fáil, with Waterford TD Mary Butler taking over from Hildegarde Naughten, who held the role between 2022 and 2024, and continues to attend cabinet meetings. Reflecting the Government’s deals with the Rural Independents Group (RIG) and the Healy-Rae brothers, two independent ministers of state – Noel Grealish and Seán Canney – will also attend Cabinet. On 12 December 2025, the Dáil passed a bill which allows for an increase in the number of junior ministers. The Bill includes the creation of three super junior minister roles, and provides for an increase in junior ministers from a record level of 20 to a new record of 23, up from 15 a decade ago. The figure includes 10 positions for Fianna Fáil, eight for Fine Gael, and five for the Regional Independent Group. Junior ministers’ attendance at Cabinet is currently subject to legal challenge, with Sinn Féin TD Pa Daly asserting that Bunreacht na hÉireann limits the number of government ministers to 15 and binds them to confidentiality about their discussions. This case is set to go to the courts by May 2025. In the meantime, People Before Profit TD Paul Murphy has sought an injunction on these members attending Cabinet until the legal verdict is delivered. |

Political reform and all-island politics

While governance remains a key theme, the 2025 PfG offers restrained commitments to political reform. Local democracy will be “enhanced,” though direct mayoral elections are no longer a listed priority. In addition, measures to increase transparency are referenced but lack a clear legislative roadmap.

Furthermore, while the previous government promised to hold a referendum on extending voting rights in presidential elections to Irish citizens in the North and diaspora, the new government has dropped this proposal and it is unlikely to go ahead. In fact, the word ‘referendum’ is only used once in the entire document.

A government of incrementalism

The new PfG is less ambitious and less specific than what was rolled out five years earlier by Micheál Martin, Leo Varadkar, and Eamon Ryan, and even what Martin and Fine Gael leader Simon Harris brought to the public in their parties’ general election manifestos. The word ‘explore’ appears 34 times and the word ‘examine’ appears 86 times in the Securing Ireland’s Future document.

The broad challenges in the housing sector – house prices, rent prices, and undersupply – have worsened since 2020, the economy stands in a more vulnerable state than it did in 2020 amid the looming implementation of US tariffs on EU exports, and the energy system continues to function with significantly higher operational costs than existed in 2020, amid the aftermath of sanctions on Russian oil and gas.

In the absence of the Green Party’s influence, it is highly unlikely that climate policy will be advanced or consolidated.

While the PfG acknowledges persistent challenges in housing, economic growth, social protection, and climate action, its proposals favour continuity over ambitious reform. Fiscal caution and broad status quoism are prioritised, reflecting a government intent on maintaining Ireland’s current trajectory rather than introducing sweeping change.