Social housing: a critical time for a new direction

National Economic and Social Council Director Rory O’Donnell outlines its proposals for reforming the social housing sector. The publication of a new national strategy opens up a real opportunity to improve how housing is provided.

National Economic and Social Council Director Rory O’Donnell outlines its proposals for reforming the social housing sector. The publication of a new national strategy opens up a real opportunity to improve how housing is provided.

The Irish Government has recently launched a new strategy for social housing. Earlier this year, the National Economic and Social Council (NESC) agreed a report – Social Housing at the Crossroads: Possibilities for Investment, Provision and Cost Rental – to assist the formulation of that strategy. It is continuing to work on other aspects of housing policy, including owner occupation, the private rented sector and sustainable urban development. This article outlines the council’s key arguments on social housing.

In each of the three channels of social provision – local authorities, housing associations and the private rental sector – there are serious challenges.

In local authorities, there is almost a total lack of new supply because of borrowing constraints. Although housing associations are seen as the main channel of future provision, there has been limited uptake of the mechanisms introduced to promote this and, in any case, this approach (as currently configured) exposes the State to rising rents in the private rental sector.

Increasing use of the private landlords to house social tenants is also problematic, as seen by rapidly rising rents, exit of low income tenants, risks of overcrowding and homelessness, State exposure to rising private rents and limited availability of secure, affordable, long-term tenancies.

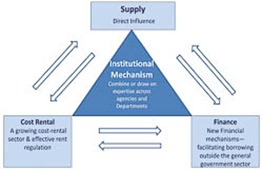

Irish policy must now develop effective approaches on three inter-related fronts: supply, finance and cost rental as shown in the figure opposite. This is what is needed to move the Irish housing system in a desirable and sustainable long-term direction.

Towards a new model

Ireland is different from other European countries in that the main providers of social housing (local authorities) are classified within the ‘general government sector’ as defined by Eurostat. Consequently, borrowing to fund new local authority housing adds to the government deficit and debt. To fund Irish social housing provision on the scale needed will require creation of public housing institutions capable of attracting finance off the public balance sheet. They would need an adequate rental income stream to meet Eurostat’s test of being in the market sector.

In addition, other countries use a range of measures to help social-housing providers access finance on favourable terms, including government guarantees and tax provisions. The Housing Finance Corporation in the UK acts as a ‘financial aggregator’ funnelling credit to the various housing associations.

Cost renting refers to a situation in which rents cover only the actual costs incurred in providing and maintaining a dwelling. It differs from profit renting, where a landlord charges the maximum obtainable rent, regardless of the historic cost.

European countries with more stable, affordable and socially-inclusive housing systems provide modest support for large-scale provision of secure rental accommodation, mostly by non-profit bodies, in which rents reflect costs. They use modest levels of capital subsidy, combined with cost rental, rent regulation and housing benefit, to provide affordable long-term rental accommodation for a large share of their citizens. In some cases, rents reflect both a degree of subsidy and rent pooling across a large mature stock, much of it built at lower cost in earlier decades. The larger social housing sector, less distinct and segregated from private rental, makes it possible to combine a mix of income groups while also making provision for those most in need.

Cost-rental provision with secure occupancy to a significant share of the population is the best available response to the dynamics of rental systems and housing markets. A movement in this direction will require adaptation of housing assistance payments: limiting the State’s current exposure to rising rents in the private rental sector and ensuring affordability for tenants currently paying differential rent.

Cost-rental provision with secure occupancy to a significant share of the population is the best available response to the dynamics of rental systems and housing markets. A movement in this direction will require adaptation of housing assistance payments: limiting the State’s current exposure to rising rents in the private rental sector and ensuring affordability for tenants currently paying differential rent.

Experience shows that in housing there are limits to reliance on passive, arm’s-length tax-based and other incentives, however smartly designed, unaccompanied by sufficient regulation and/or direct public policy action. If, as government wishes, housing provision is no longer to be developer-led, it will have to be led by some other identifiable actor or actors. But in the current economic environment and institutional context it has become even more difficult to achieve plan-led development.

However, the State now has considerable land resources that can be used for social housing – land owned by local authorities and the Housing Agency, under the control of NAMA and other bodies. Direct influence on supply is critical to ensure that available finance is actually taken up in new projects and that rent regulation works with, rather than against, the market.

New institutional arrangements will be required to move policy on each of the three fronts. The creation of a ‘financial aggregator’ or special purpose vehicle to facilitate off-balance sheet borrowing will make finance available. But such a vehicle will require an engine capable of planning, driving, delivering, allocating, protecting and maintaining the supply of affordable rental homes.

What body or bodies will be the engine, performing these roles or co-ordinating their execution by others? There are doubts about whether several of the key housing functions can be performed by the actors as currently configured: the housing associations, planners, the construction sector and the banking system. While there is, on paper, a strong logic for institutional investors, in search of long-term returns, to invest in rental housing provision, it remains to be seen whether this materialises.

Ireland needs to create institutions capable of achieving a resumption of provision by the local authorities or an equivalent body, such as a national housing trust, working with voluntary housing bodies. This would combine the capabilities developed in NAMA, the Housing Agency, the local authorities and other bodies – as is emerging in current policy initiatives.

The conditions that made the elements of Ireland’s traditional approach effective and sustainable – fully funded local authority provision, differential rent in a secure local-authority tenancy and tenant purchase – have largely disappeared. For several decades, there has been insufficient investment in new social housing provision. As a result, policy relies on a strong queuing system and greatly increased, unsatisfactory, reliance on the private rental sector. There has been an unstable policy compromise involving a wish to retain differential rent and tenant purchase, combined with budgetary pressure to limit spending on rent supplement and leasing. This may now be coming to an end, with a substantial allocation of capital resources for housing provision in the recent Budget and a comprehensive new social housing strategy.

Given the State’s high level of involvement in property, land, finance and investment – arising in part from the need to respond to the crisis – there is now a once in a generation opportunity to take on this challenge.