Solving climate change

Dieter Helm contends that climate change can be solved but current policy is failing. He talks to eolas about his alternative: real carbon pricing, a shift from coal to gas and more R&D.

Dieter Helm contends that climate change can be solved but current policy is failing. He talks to eolas about his alternative: real carbon pricing, a shift from coal to gas and more R&D.

Climate change policy is not tackling global warming and will not work without a radical shift towards cutting coal. That’s one of the key messages from Dieter Helm, professor of energy policy at Oxford University and author of ‘The Carbon Crunch’.

Helm’s ideas are timely as energy moves up the political priority list. Speaking to eolas, he predicted: “We’re heading towards a very serious capacity crunch in 2015-2016. Demand will probably turn out to be significantly higher than projected and supply can only go down because nothing can be added between now and then.”

Overarching policy is “in a great state of flux” and “everyone in Europe is moving back away from subsidising wind and current generation solar.” The crucial turning point will be the European Parliament elections. A new Commission will take office and the focus will be on jobs, competitiveness and the shale gas question.

Helm then expects a fundamental review of UK energy policy after the 2015 British general election, including more discussion about whether the technologies identified as “winners” should be pursued. He outlined his conclusions at the Environment Ireland conference. In his view, three “very simple questions” are largely avoided in the current literature and discussion:

1. why have emissions been going up?

2. why has virtually nothing been achieved since 1990 in addressing climate change?

3. what would we need to do if we seriously wanted to address climate change?

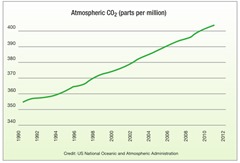

Despite all the political and public commitment since 1990, carbon emissions keep going up and currently stand at 400ppm. The rate of growth is now approaching 3ppm per year and an atmospheric concentration of 450ppm will increase the global temperature by more than 2°C.

Despite all the political and public commitment since 1990, carbon emissions keep going up and currently stand at 400ppm. The rate of growth is now approaching 3ppm per year and an atmospheric concentration of 450ppm will increase the global temperature by more than 2°C.

Emissions are going up because more coal is being consumed. The share of coal, in the world’s energy supply, has gone from 25 per cent to almost 30 per cent over the last two decades. The Chinese economy – by far the world’s largest consumer of coal – is five times larger than it was in 1990.

Energy-intensive industries have migrated from the West to China and Chinese exports (produced by coal power) are consumed in large quantities by Europeans and North Americans.

“We think that because our carbon production’s gone down, that somehow our carbon footprint has gone down too,” he commented but this is far from true. UK emissions fell by 15 per cent between 1990 and 2005 but UK carbon consumption went up by 20 per cent, when imports are factored in.

“Arguably, our policies made carbon consumption higher than it otherwise would have been,” Helm noted. “It’s carbon consumption that matters, not carbon production. And once you look at carbon consumption, you get a completely different picture of the carbon responsibilities around the world.”

The coal question

Continuing to consume coal at present rates “is not something that this planet can sustain.” This is sustained by three new coal-fired power stations per week in China and India combined which will, unfortunately, make all renewable energy “utterly trivial”.

Policy must be framed around limiting carbon emissions to 450ppm. According to Helm’s analysis, this means bringing global coal consumption back to 1980 levels – and making this shift by 2035. Any serious global warming framework also needs to account for another 2.5 billion people living on the planet, mainly born in China, India and Africa.

At the 2011 UN climate change conference in Durban, ministers decided to wait until 2015 to decide what action would be taken after 2020.

The world economy though is moving ahead much more quickly. 400-600GW of new coal are expected to come on to the Chinese and Indian energy systems alone by 2020. If current growth continues, China’s GDP is due to double in the same timeframe.

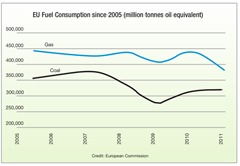

Europe’s renewable record is undermined by a new “substantive dash for coal”. As all renewable sources are intermittent, they need another fuel to provide extra power at off-peak times. Coal, gas and nuclear can all provide that baseload but their carbon emissions vary.

Europe’s renewable record is undermined by a new “substantive dash for coal”. As all renewable sources are intermittent, they need another fuel to provide extra power at off-peak times. Coal, gas and nuclear can all provide that baseload but their carbon emissions vary.

Germany is moving from zero carbon generation – using “some of the safest and most highly regulated reactors in the world” – to coal and also moving from gas to coal consumption.

This involves building 7-8GW of new coal-fired plant, including a heavily polluting 2GW lignite plant. Helm remarked: “The existing coal power stations are running flat out and new coal stations need built across Europe.”

Current renewable technology is expensive and cannot be built on the scale needed to solve climate change.

David MacKay, the UK Department of Energy and Climate Change’s Chief Scientific Advisor, estimates that replacing half of the energy used by Britain’s cars would mean building a 4km strip of wind turbines around the British coastline.

Helm accepts an economic case for building wind farms but this is an entirely different issue from their contribution to tackling climate change. The economic contribution, though, is itself offset by the EU emissions trading system (EU-ETS) which allows the carbon price to fluctuate significantly.

At the Copenhagen conference, the final deal was drawn up by the USA and China and Europe was side-lined. In 2015, the Chinese and the Americans will be “absolutely pivotal” in making the main decisions.

In summary, Helm finds that European energy and climate change policy has reduced competitiveness and security, and increased cost, carbon consumption and energy demand without tackling the causes of global warming.

America’s carbon cuts

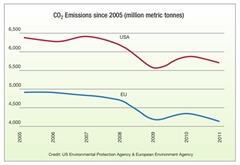

Environmentalists often dismiss the USA a major polluter and contributor to climate change.

However, in a surprising but significant trend, American carbon emissions are falling very sharply – by investing in new technologies and getting out of coal and into gas.

This is not the “long run answer” but gas produces half of the emissions produced by coal and is therefore much better for tackling the cause of climate change.

The energy cost ratio between Europe and the USA is 4:1 in America’s favour, making it more attractive for new industrial investments. The ratio between the USA and China is similar and outweighs the Chinese labour cost advantage: “That’s why re-shoring is taking place on an enormous scale of energy-intensive industries [coming] back to the United States which, along with Canada and Mexico, is moving to a state of energy independence.”

Alternative

As explained, Helm agrees with the scientific consensus that climate change is man-made. The policy thrust, in his view, must recognise that climate change is the greatest problem of the 21st century and the climate must be stabilised for future generations. His alternative approach is three-fold:

1. Establish an effective price for carbon

1. Establish an effective price for carbon

The polluter pays principle should not just apply to those who produce emissions: “We are the polluters. We do the consuming. Carbon consumption has to be taxed.” A border tax adjustment would increase the cost of carbon-intensive imports coming into Europe. Without this change, China will continue to subsidise its exports and distort trade – by not charging a carbon price.

This can be done relatively easily. The bulk of traded carbon comes from fertilisers, chemicals, aluminium and steel. A border tax adjustment is permitted under WTO rules, which allow for environmental measures and are meant to tackle trade distortion. The EU ETS price is short-term, volatile and low but an effective carbon price must be long-term, stable and rising. “Start low because you’ve got the existing capital stock,” he advises. “You let it rise through time.”

2. Get out of coal

Gas is the only substitute for coal that can be introduced quickly in a way that economies can handle, as America’s example shows. Unconventional gas exists around the world and, as explained, gas emissions are much lower than coal emissions. Shifting from coal to gas would gain some extra time for dealing with the main problem of global warming.

3. Invest in new technologies

Helm concludes that no existing technologies can solve climate change, apart from large scale nuclear generation which is politically unacceptable. There are, though, “very promising grounds for optimism” in new technologies.

Next generation solar, in his view, is probably the most promising one. Scientists are opening up the rest of the light spectrum and “an almost infinite supply of energy is out there.” Smart grids, new battery technology, transport electrification, biotechnology and carbon capture and storage also offer potential. Increased R&D funding can come from setting aside a small proportion of the large budget for renewable subsidies.

“The only way we’re going to go forward is to leave the fossil fuels in the ground,” he says, looking to the long term. “The only way we’re going to leave the fossil fuels in the ground is if we have bulk energy technologies which can compete with them.”

In conclusion, he noted that climate change is a “completely solvable problem but not on current energy and climate policies.” The extra problem is: “We don’t have the luxury of time. It’s 400ppm already and we have to stop the march to 450 or 500.”