Taxing times

New research highlights the gap between headline corporate tax rates and what companies actually pay. Emma Blee reports.

New research highlights the gap between headline corporate tax rates and what companies actually pay. Emma Blee reports.

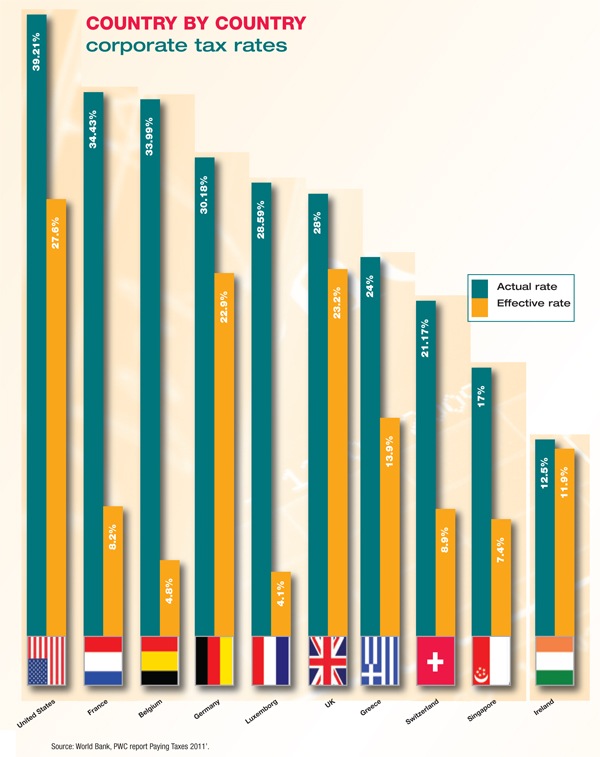

Amid pressure to raise the level of corporation tax in Ireland in return for lower interest on bailout loans, a World Bank-PwC report has revealed that the rate of effective tax in other countries is much lower than in Ireland.

The actual rate of corporation tax is the official figure which is set by the Government but the effective – or headline – rate is the level that most companies pay. The effective rate gives a more accurate picture of taxation as it takes depreciation and a range of exemptions and reliefs into account.

Ireland’s actual rate of 12.5 is much lower than countries such as France, Germany and the UK, which are all set at around 30 per cent. However, figures contained in ‘Paying Taxes 2011’ suggest that what many countries pay in corporation tax is well below the actual rate. The study was based on a hypothetical domestic company with no imports or exports.

In France, the effective rate is 8.2 per cent, in Luxembourg it is 4.1 per cent and in Germany the rate paid is 22.9 per cent. The Irish effective rate, at 11.9 per cent, is very close to its actual rate.

To achieve a low effective rate, businesses would have taken advantages of credits and allowances within the various countries.

For example, in France there is a wide range of tax breaks and incentives, including credits for hiring older workers and setting up in a poor region as well as a hefty research credit of 30 per cent. Ireland, however, does not have the same range of write-offs that other countries do.

However, Jim Stewart, a senior lecturer in finance at Trinity College Dublin, claims 61 per cent of companies here pay no tax at all – this includes small to medium- sized businesses that are not making any money because of the recession ␣ and just 0.8 per cent of companies pay 84 per cent of corporate tax.

Stewart believes that the hypothetical French company adopted in the report is much smaller than the average business and does not reflect reality: “It’s not actually a real company and it uses various assumptions. It’s not a measure of effective tax rates; it’s a measure of assumptions.”

He adds that measuring the effective rate of tax is “difficult” and very specific data from company accounts would be required to provide accurate results.

Attracting investment

Ireland’s low corporate tax rate has become its main offering to attract foreign investment. France and Germany, though, have been calling for an increase in Irish corporation tax, claiming that it has an unfair competitive advantage in luring multinational companies.

At a meeting in Brussels in March, Nicolas Sarkozy said it is “difficult to ask other countries to bail out Ireland when Ireland is determined to keep the lowest tax on profit in Europe”.

Speaking about the attempt to use the terms of the bail-out to force a change in the rate, Enda Kenny said: “These two things are entirely unrelated.” He argues that European treaties make clear that tax levels are a matter for individual nations to decide.

Under tax reform proposals, the European Commission is also investigating the possibility of a common consolidated corporation tax base (CCCTB), which it hopes would make Europe more attractive for business.

The common tax base would mean that companies could access their tax bills across Europe under a single set of rules and profits would be shared between the different countries under an agreed formula. It would also include the ability for companies to write off losses in one country against profits in another.

Under the plans, each state would still charge their own rate of corporate tax on those profits. It is not yet clear if the CCCTB will be optional.

While Enda Kenny called it “harmonisation through the back door”, he has agreed to engage on the proposals. He argues that the plans could make it difficult for companies to attribute profits to Ireland, which would dilute the impact of the low corporate tax rate.