The 27th Seanad

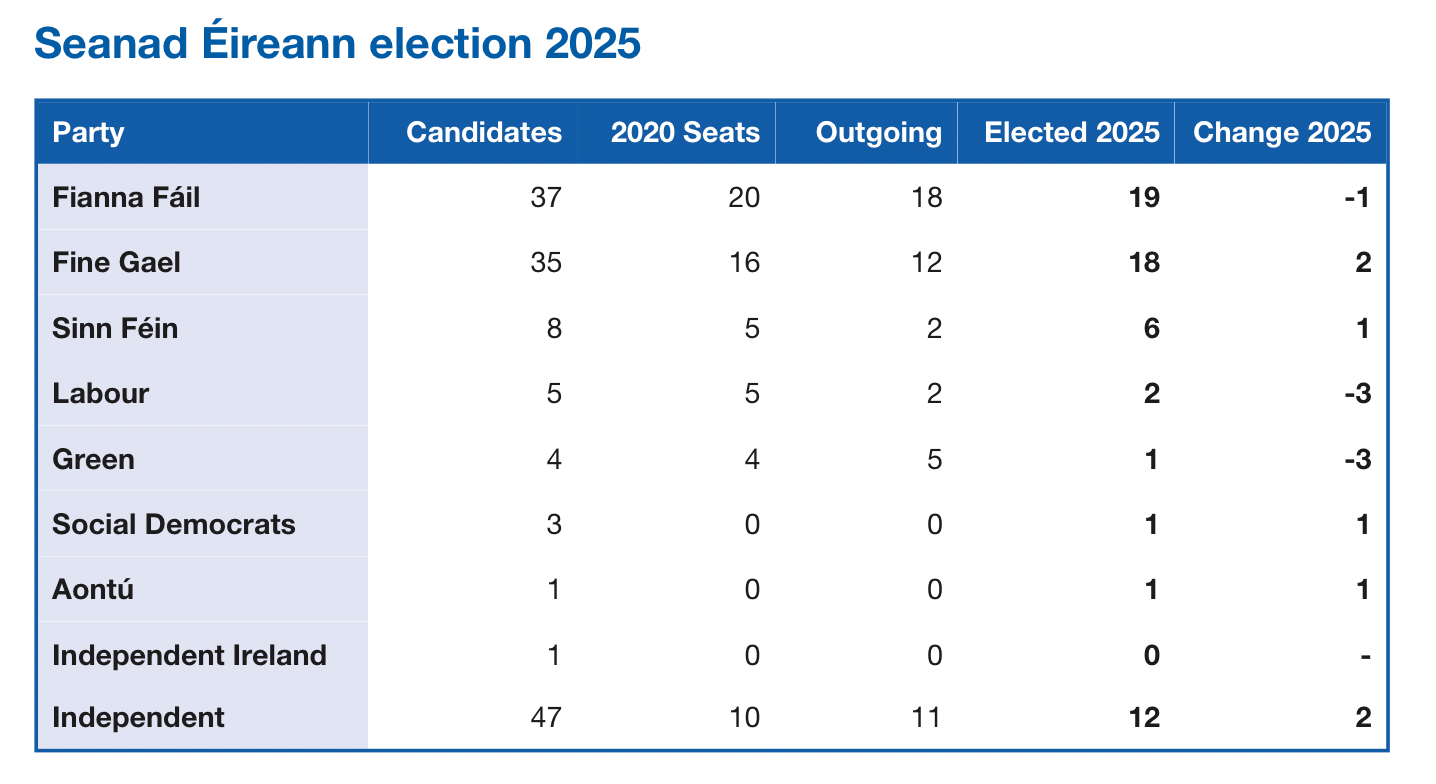

All 60 members of the 27th Seanad have now been either elected or appointed, with a record number of women taking their seats in Ireland’s upper house.

For the most part, the status quo will prevail in the Seanad, with the members of the upper house being dominated by Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael. The two parties combined have 37 (62 per cent of the seats) members, of which 11 are direct appointments by the Taoiseach.

While Sinn Féin, in raw numerical terms, scored a solid if unspectacular result in the elections, it will be relieved at having found a role for two ousted former TDs – Chris Andrews and Pauline Tully – as well as electing one of its most high-profile northern Executive figures, former Minister for the Economy, Conor Murphy.

There were causes for celebration among the Social Democrats and Aontú in particular, as they made are set to make their debuts in Seanad Éireann. Labour – in spite of a broadly successful general election result – will be disappointed at having went from electing five Seanadóirí in 2020, to only two in 2025.

A notable result for the Green Party – which was virtually wiped out in the general election – was the return of Malcolm Noonan – erstwhile junior minister at the Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage in the previous government – to the Oireachtas.

Female representation and minorities

The new government has been criticised by opposition figures for the lack of women at Cabinet level, with only five of the 19 TDs (26 per cent) attending cabinet being women. In addition, only six of Fianna Fáil’s 48 TDs are women, while Fine Gael has 10 female TDs out of a total of 38.

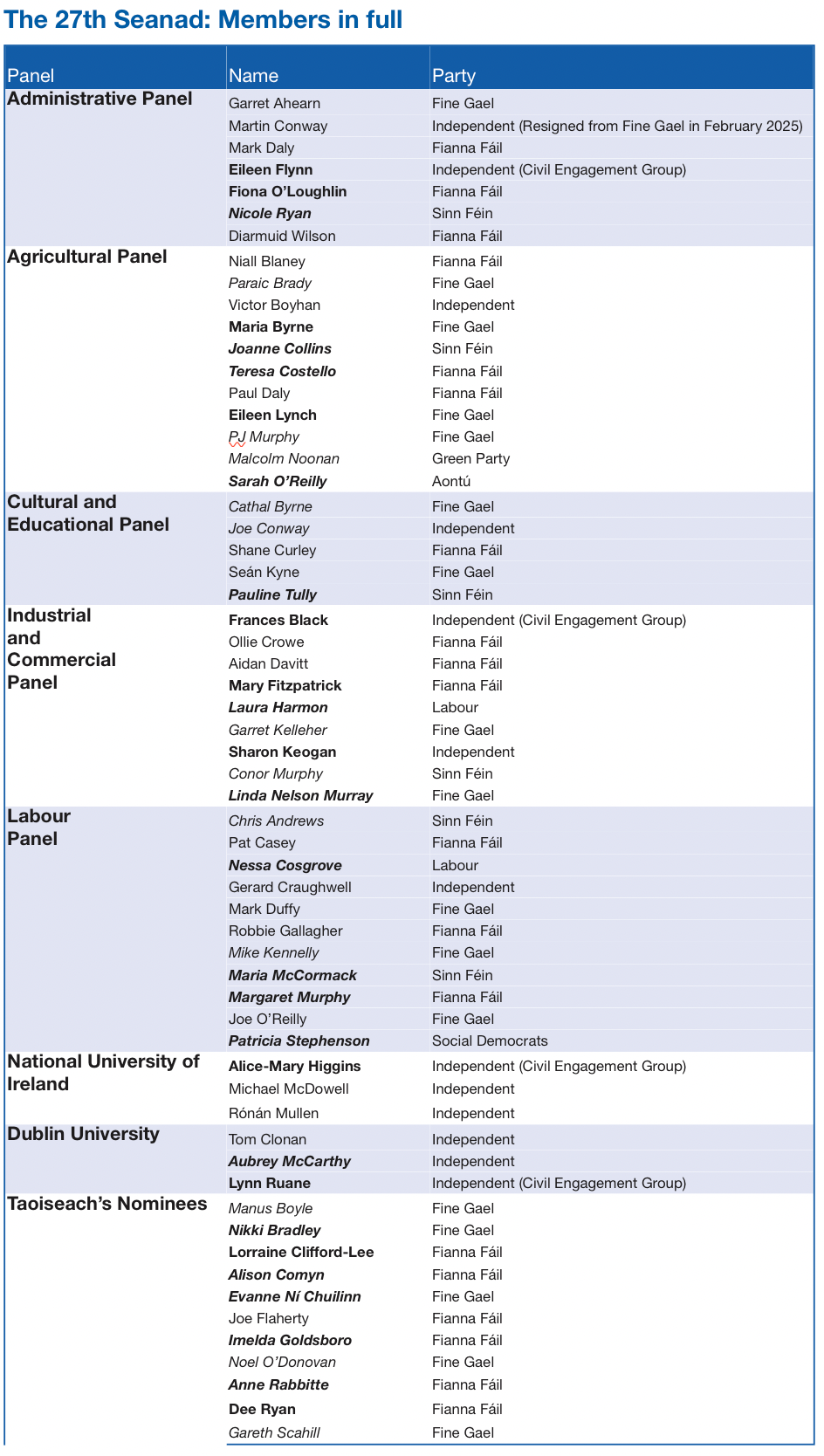

In the Seanad, however, Fianna Fáil has a much higher percentage of female senators compared to its proportion of female TDs, with nine (47 per cent) of Fianna Fáil’s 19 senators being women. Five (29 per cent) of Fine Gael’s 17 senators are women, and out of the 13 independent senators in the new Seanad, five (38 per cent) are women.

Four parties have a majority of women among their groups of senators. These are:

- Sinn Féin (four out of six);

- Social Democrats (one Senator who is a women);

- Labour (two senators, both women); and

- Aontú (one senator who is a women).

Overall, there are 26 women in the new Seanad, giving a female representation rate of 43 per cent, a record high number for either chamber in the Houses of the Oireachtas. This can be compared to a female representation rate in the Dáil of 25 per cent.

Elsewhere, only one senator, Eileen Flynn, is from an ethnic minority background. Flynn is the first female Irish Traveller to be elected to either house in the Oireachtas.

The Seanad has historically been utilised by Irish governments to integrate northerners into the political process. While the government parties have not appointed or elected any senators from the North, the Social Democrats’ successful candidate, Senator Patricia Stephenson, was born in Belfast and Sinn Féin successfully elected County Armagh’s Conor Murphy.

What can senators do?

Speaking to eolas Magazine in December 2024 (issue 67), Senator Alice-Mary Higgins explained the fundamental differences between the role of a Senator and the role of a TD: “As a Senator, you have a national constituency and a more thematic focus.

“One interesting difference is that in the Dáil committee stage of a bill, where most amendments are made, is usually debated by just a few TDs from a relevant committee, whereas in the Seanad, every bill from every department must go through the whole house and every senator gets to debate and vote. That means the Seanad can often join the dots in a different way.”

Rather than a conventional checks and balances role, the Seanad is more like the British House of Lords, albeit slightly more democratic. It scrutinises legislation and has an important role in the amendment process of passing legislation, as seen in the passage of the Planning and Development Act 2024, when Seanad amendments accounted for an additional 175 pages of the legislation. However, unlike the House of Lords, while the Seanad can delay a bill for 90 days, it seldom exercises this ability, with the Seanad only opposing the Dáil on two occasions, and not since 1959.

The Seanad has survived three significant shocks in its history:

- 1928: Removal of direct elections under the Free State government, which simultaneously enhanced its powers.

- 1937: Facing a Seanad which was proving to be problematic for the passage of his government’s legislation, former Taoiseach Éamon de Valera ensured that the newly ratified Bunreacht na hÉireann provided clarity that the Dáil was the house with the legitimacy to pass legislation.

- 2013: The Government tries to abolish the Seanad entirely. Following passage of the 32 Amendment Bill 2013, the Irish people voted to retain the Seanad, in spite of the stance of the Taoiseach of the day, Enda Kenny, who supported abolition.

Bunreacht na hÉireann presented a major curb on the powers of the Seanad, ensuring the level of checks and balances afforded to the Seanad were minimal, whilst providing for a number of technical measures from which the Seanad can avail, although these have rarely been enacted.

Indeed, only on two occasions has the Seanad voted against a Bill which was passed by the Dáil. In 1958, de Valera proposed a first-past-the-post electoral system which could have increased Fianna Fáil’s majority in the Dáil. Whilst this Bill was passed in the Dáil in 1959 by a majority of 19, the Seanad rejected the Bill by a majority of one.

Despite this opposition, the Dáil availed of its power to pass legislation which had been rejected by the Seanad after 90 days, with the proposal eventually being defeated in a referendum in 1959.

In its modern form, the Seanad has the powers to delay a bill by up to 90 days, whereas the original Seanad which operated in the Free State had the power to delay legislation by an initial period of up to nine months, which was extended in 1928 to a period of delay of up to 20 months. The aim of this this was to provide an enhanced level of checks and balances.

Changing of the guard

11 of the members of the previous Seanad won election to the Dáil in the concurrent general election, while 14 members of the previous Seanad decided not to run for re-election, and have left politics.

Notable names among these include former Fianna Fáil senator Lisa Chambers, who bows out of politics for the time being after a political career which – once highly promising – devolved into failure. Chambers failed to be elected to the Dáil for the second general election in a row and was an unsuccessful candidate in the European elections in 2024.

The new Seanad has a marked general shift between the new crop of senators, and those who took their seats in 2020. The previous Seanad included Fine Gael’s Paddy Burke (1993), Fianna Fáil’s Denis O’Donovan (1989), and independent David Norris, all of whom were elected in the 1980s and 1990s. All the members of the 27th Seanad first took their seats in the 21st century, with the longest serving incumbent senator now being Fianna Fáil’s Diarmuid Wilson, who has been in the house since 2002.

** Female members in bold