The creation of Northern Ireland: Home rule for unionists

Current debates over the future of the union, which focus on the question of Scottish independence, and what format it might take, display a noticeable ignorance of the history of the last occasion upon which the union was sundered, writes historian Marie Coleman.

The transfer of devolved powers to the newly created Northern Ireland 100 years ago, on 3 May 1921, represents one of the greatest ironies of modern Irish history. Ulster unionists, initially implacable opponents of home rule for Ireland, became the first political grouping on the island to be granted this form of self-government within the United Kingdom.

Ireland, Ulster and the United Kingdom were partitioned under legislation passed at Westminster in December 1920 and officially entitled, unduly optimistically as an ‘Act to Provide for the Better Government of Ireland’. This was the fourth effort by successive British governments to introduce home rule to Ireland. William Gladstone’s first home rule bill was defeated in the House of Commons in 1886 by the first serious manifestation of Irish political unionism, supported by Conservatives and a unionist faction within Gladstone’s own Liberal Party. His second effort passed the first hurdle of the Commons in 1893 to be defeated by what then seemed a permanent and unassailable pro-union majority in the House of Lords.

It was not until 1912, after the truncation of the Lords’ veto power under the 1910 Parliament Act, enacted in response to the upper house’s attempt to block the socially reforming aspects of David Lloyd George’s 1909 budget, that the question of Irish home rule returned to the political agenda at Westminster. The abolition of the Lords’ permanent veto, and the political arithmetic in the Commons, where HH Asquith’s Liberal government relied on the support of John Redmond’s Irish Parliamentary (i.e. home rule) Party, made the introduction of home rule in Ireland by 1914 a realistic prospect.

A tripartite campaign of parliamentary, populist and paramilitary opposition by Ulster unionists could not prevent the third home rule bill becoming law on 18 September 1914, but did succeed in extracting a promise in principle of excluding Ulster from its provisions. The nature of such exclusion, in terms of territory and duration, were not specified as the outbreak of the First World had necessitated the postponement of the act’s practical application.

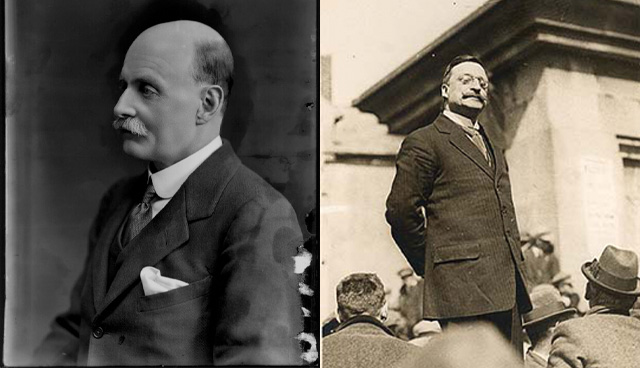

Further attempts to introduce home rule in the summer of 1916, to quell popular unrest in nationalist Ireland after the Easter Rising, and a suggestion of sweetening the pill of abortive conscription in 1918 with a simultaneous introduction of home rule, failed, largely due to Irish nationalist distrust of the chief protagonist in both cases, David Lloyd George. When the war ended in 1918 the British Government returned to the prospect of legislating for Irish home rule. Too much had changed in Ireland during the preceding four years to simply resort to a delayed enactment of the 1914 legislation and a committee was formed under the chairmanship of the former Irish unionist leader, Walter Long, to advise the Government on how to proceed.

The report of the Long committee, presented to the Government in November 1919, recommended scrapping the 1914 home rule act and replacing it with a new one. Unlike the three previous home rule bills, this one recommended a partitionist solution to the entrenched ethno-political cleavage in Ireland. Long envisaged two home rule parliaments for Northern and Southern Ireland, the first with jurisdiction over the entire nine counties of the province of Ulster and the second over the remaining 23.

“Almost 80 years before the establishment of the Scottish Parliament and Welsh Assembly a region of the UK established its own parliament, government and bureaucracy, which it ruled largely free of Westminster interference for fifty years.”

The partitionist solution to the Irish question reflected the extent to which this option had gained ground since 1914. When the idea was first mooted in 1912 by the Liberal back-bench MP for St Austell in Cornwall, TG Agar-Robartes, it was rejected out of hand by both nationalists and unionists. To nationalists, Ireland was a single and indivisible entity, while unionists sought the preservation of the status quo, with Ireland remaining as integral a part of the United Kingdom which was created in 1801, as were Scotland and Wales.

The unionist U-turn on home rule between 1912 and 1920 was a pragmatic acceptance that circumstances had changed and the status quo could not be maintained. The Easter Rising and War of Independence deepened unionist distrust of and the desire to distance themselves from southern nationalism, while the determination of successive British governments to legislate for home rule convinced unionists that they could no longer trust the national government to be the best guarantor of unionist interests. The best solution was to take control of their own destiny.

This situation was summed up effectively by the Unionist MP for Antrim South, Captain Charles Curtis Craig, whose brother, James, would later serve as Northern Ireland’s first Prime Minister. In the Westminster parliamentary debate on the provisions of the Government of Ireland bill, CC Craig admitted that unionists “would much prefer to remain part and parcel of the United Kingdom … but we have many enemies in this country, and we feel that an Ulster without a Parliament of its own would not be in nearly as strong a position as one in which a Parliament had been set up”. Effectively, Ulster unionists had appropriated the logic of Irish nationalism and applied it to their own situation.

The legislation which evolved from the Long committee’s report differed from the original proposal in one significant way; the suggested 23-nine county partition was replaced with the division between 26 and six counties which endures to the present day. The delineation of Northern Ireland in this way was the most beneficial to ensure Ulster unionist political and electoral dominance. In 1911, the census showed that the population of the entire province of Ulster was 43.7 per cent Catholic, uncomfortably large for unionist security. Even within the six counties, Fermanagh and Tyrone each had Catholic majorities of around 55 per cent. A four-county Northern Ireland, while copper-fastening unionist control, with an even safer Protestant majority, might be too small to be viable. The perceived treachery of British politicians made unionists wary of the northern rump remaining fully within the legislative union while southern Ireland went its own way.

“The unionist U-turn on home rule between 1912 and 1920 was a pragmatic acceptance that circumstances had changed and the status quo could not be maintained.”

As such partition was not just the division of the island but also of the province of Ulster. In adopting a utilitarian approach of achieving the greatest good for the greatest number, Ulster unionists effectively cut adrift substantial unionist populations in the ‘border counties’ of Donegal, Cavan and Monaghan, in addition to a smaller cohort of southern unionism in the three southern provinces.

Furthermore, the 1920 Act represented the partition of the United Kingdom. Later in 1921 when the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed in December, coming into full effect in December 1922 and establishing the 26-county Irish Free State as a dominion of the commonwealth, the geographical boundaries and the name of the United Kingdom were altered after 120 years. What would henceforth be the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland lost 25 per cent of its land mass and 7 per cent of its population.

This wider British dimension to partition is not well understood and there appears to be either a failure or unwillingness to recognise the impact of southern Irish independence on the United Kingdom. Current debates over the future of the union, which focus on the question of Scottish independence, and what format it might take, display a noticeable ignorance of the history of the last occasion upon which the union was sundered.

Another British dimension, that receives similarly less attention, is how the 1920 Government of Ireland Act introduced a significant innovation within the British constitutional sphere; the creation of Northern Ireland was the first initiative in devolved government within UK governmental structures. Almost 80 years before the establishment of the Scottish Parliament and Welsh Assembly a region of the UK established its own parliament, government and bureaucracy, which it ruled largely free of Westminster interference for 50 years.

Northern Ireland’s experience of devolution exhibited the flaws inherent in many previous plans for Irish home rule. Commenting in 1912 on the legislative limitations of the third home rule bill, the then Sinn Féin leader, Arthur Griffith, declared that “if this is liberty the lexicographers have deceived us”. In marked contrast to the measure of independence which dominion status conferred on the Irish Free State, a significant range of services were reserved to Westminster, including the crown, foreign affairs and foreign trade, the armed forces, postal services, trademarks, lighthouses and coinage.

The limitations of home rule were most obvious in regard to finance. While Northern Ireland had expenditure powers, it did not have commensurate revenue-raising abilities. In practice, this meant that the government did not know how much income it would have to spend. Frequently, throughout the 1920s Sir James Craig’s government relied on subventions from the London Exchequer. The situation was exacerbated by a post-war economic downturn, hastened by decreasing market for Northern Ireland’s heavy industrial product, and consequently the highest unemployment rates in the UK during much of the inter-war period.

“It seems unlikely that many of those who oversaw the creation of Northern Ireland in 1921 would have expected it to reach its centenary.”

In practice, while Northern Ireland legislated separately from Great Britain, many measures were simply adopted as Northern Ireland-specific versions of the original British legislation. This was most notable in regard to the post-Second World War social reforms in areas such as health and education, which allowed Northern Ireland to keep pace with the rest of the United Kingdom and benefit from the most significant social reforms introduced there in the twentieth century. While the socialistic ideology underpinning many welfare state provisions sat uncomfortably with the conservatism of unionism, strengthening the connection with Britain and further distancing Northern Ireland from the Republic were benefits which far out-weighed such concerns.

The largely distant relationship between London and Belfast allowed for sufficient flexibility to respond to local circumstances; for example, conscription was never extended to Northern Ireland during the Second World War due to nationalist and Éire sensitivities. Conversely, the hands-off approach also applied when the unionist government unilaterally altered a key provision of the Government of Ireland Act in 1929 by abolishing proportional representation for parliamentary elections. Arguably the non-intervention of the British government enabled what many nationalists interpreted as the discriminatory excesses of the Stormont government between 1921 and 1972.

It seems unlikely that many of those who oversaw the creation of Northern Ireland in 1921 would have expected it to reach its centenary. The period of greatest threat to its survival was between 1921 and 1925 during which it endured a period of intense communal sectarian violence and the threat from the irridentist Free State that was only quenched when the 1925 boundary commission report finalised the existing 26-six county divide. Commentary during the current centenary has questioned whether the region will survive in its current form to mark another significant chronological milestone. The answer to that question may lie elsewhere as the dynamics of the wider union remain in flux in response to Brexit and the rise of nationalist sentiment within Scotland, England and even Wales. Perhaps to question to ask now is not about the survival of Northern Ireland but of the United Kingdom.

Dr Marie Coleman is a Reader in modern Irish history at Queen’s University Belfast and a member of the historical panel advising the Northern Ireland Office on the centenary of the creation of Northern Ireland.