The housing market

Assistant professor of economics at Trinity College Dublin, Ronan Lyons, discusses future demand in Ireland’s housing market and how a cooling of inflation in the sales market is not being reflected in the rental sector.

After five years of tight supply driving up prices in the sales market, recent evidence suggests that greater levels of supply are cooling market inflation, especially in Dublin. However, this picture is not replicated in the rental market, where despite Rent Pressure Zone legislation, no improvement in supply has led to no letting up in inflation.

Lyons explains that this demand is only set to increase, driven by four main sources of housing demand including: population increases; net migration; obsolescence and changing demographics.

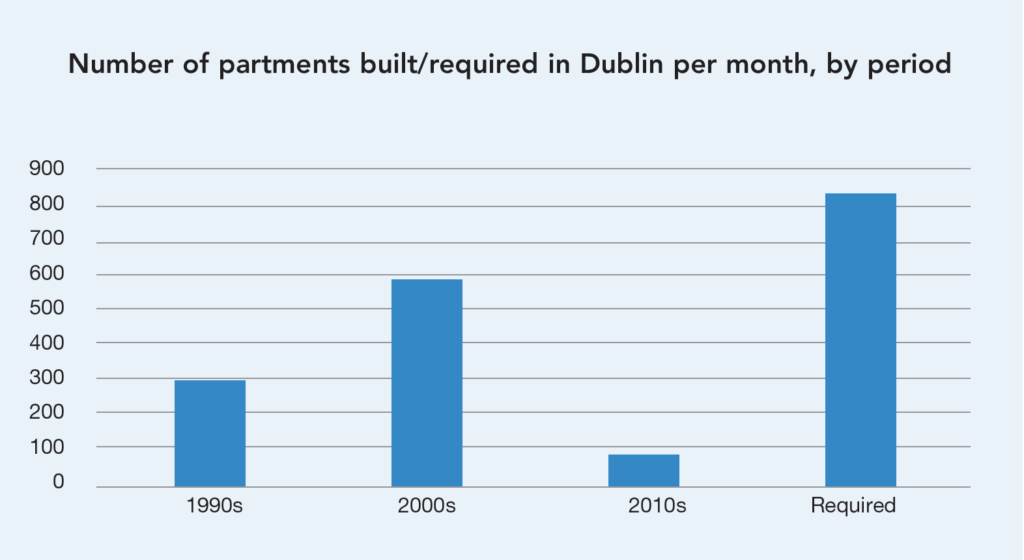

Discussing the predicted population increase, Lyons highlights the contrast between a 1990s Ireland which had moderate levels of natural population increase and some net migration to the 2000s when both were significantly higher and an extra 50,000 homes were required.

Since 2010, while the natural increase in population remains high, it has been falling slowly and this is a trend set to continue over coming years. Lyons estimates that to meet this need alone, Ireland will require over 20,000 new households per year.

Added to this, Ireland has returned to positive net migration. Ranking as the most volatile major economy in Europe in terms of net migration figures, Ireland’s current figures are positive and top up the fall in natural population increase. Combined, Ireland’s projected population increase and net migration figures suggest a requirement of at least 30,000 homes per year.

However, these figures alone do not determine demand in Ireland. Changing household size is also a major factor in determining the requirements to meet growing need. As Lyons notes, Ireland is following a similar trend to most major European countries in recognising a reduction in the number of people per household. In the 1960s the average household contained 4.2 people, compared to a 2.7 person rate currently and a predicted 2.2 person rate by 2060.

This decrease is caused by a range of issues including the longevity of life expectancies, families having fewer children and people delaying having children until later in life. Lyons highlights that this is a trend common across the high-income world but one that Ireland is approaching slower than most countries. This trend is expected to increase housing demand further by another 10,000 to 15,000 homes per year on top of what is required for natural increase.

As well as this, a further 10,000 to 16,000 dwellings are required for obsolesce. “Even in a country like Italy, that has stable demographics and a falling population they still need to build new homes every year because existing housing stock is falling out of use. This occurs due to age of stock but also because of internal mobility, meaning people moving into bigger cities. Ireland is a laggard in terms of urbanisation but we are progressing and so will have a higher obsolescence problem than other countries,” explains Lyons. “Over the next half century Ireland’s obsolescence rate is set to be between 0.5 to 0.8 per cent, which will require 10 to 15,000 homes per annum just to stand still.”

“Our labour market is as urban as our peers, our housing market is not.”

Lyons admits that an overall demand of 50,000 homes per annum for the foreseeable future is a conservative estimate with the potential for the Irish system to need up to 60,000 homes to accommodate these main sources of housing demand.

Pointing to a significant shortfall in the Government’s targets and estimated demand, Lyons explains that recent improvements in the rate of dwellings commenced still fall well short of underlying demand.

“Comparing our stock of dwellings with our population, Ireland has no shortage of houses. Rather, it is missing about 500,000 apartments.”

However, rather than simply addressing volume, Lyons argues that the mix of housing in Ireland needs to be tailored to emerging trends. “Comparing our stock of dwellings with our population, Ireland has no shortage of houses. Rather, it is missing about 500,000 apartments,” he states.

Elaborating on this further, the economist outlines a surplus of family homes but a shortage of dwellings for one or two persons. Yet, almost half of housing being built in Ireland per quarter currently falls under the rural or ‘one-off’ category. “Only a tiny fraction (12 per cent) are urban apartments, which is where most of the need is,” he states.

Lyons highlights that an analysis of planning permission shows an expected uptick in supply of estate housing and apartments, but adds: “The problem with apartments is that it is at least three years away and not all of that is going into the rental sector. A lot of it will facilitate downsizing, which is needed, but we also need build-to-rent stock as well.

Between 1960 to 2016, Ireland currently ranked last out of the OECD countries in the urbanisation rate. Describing the country as a “demographic outlier”, Lyons stresses that Ireland is currently as urbanised as the other wealthy OECD countries.

Lyons states that Ireland’s under-urbanisation is a housing market problem, not a labour market one.

“Our labour market is as urban as our peers, our housing market is not,” he says. “Consequently, we have the worst sprawl in Europe, which is not sustainable.” Lyons suggests that the preferred political solution of locating jobs outside of Ireland’s major cities is not compatible, instead he believes that there is little evidence that Dublin’s population share is too big, as claimed by some, instead pointing to across Europe where growth of the largest cities has proven a rise for smaller cities.

Concluding with an estimate of what Ireland requires to meet growing need, Lyons suggests that population growth, demographic change and urbanization are likely to require a need for new smaller dwellings until the 2080s. He points to Eurostat’s estimate that Ireland’s population will grow to 6.2 million by 2080, added to the fact that Ireland is set to be 80 per cent urban with an average household size of 2.2. This is in addition to the current backlog of smaller dwellings, with 25,000 needed per year to 2040.

“By then Ireland’s five largest cities will house five million people, mostly in one to two person households and the country will need 1.9 million apartments. In Dublin, that equates to one apartment block every week until 2080s.”