The pathway to a decarbonised society

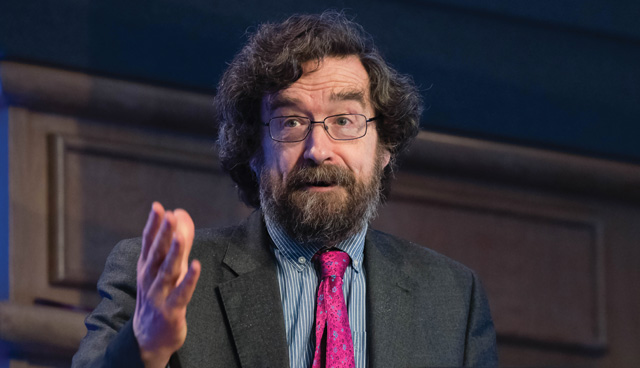

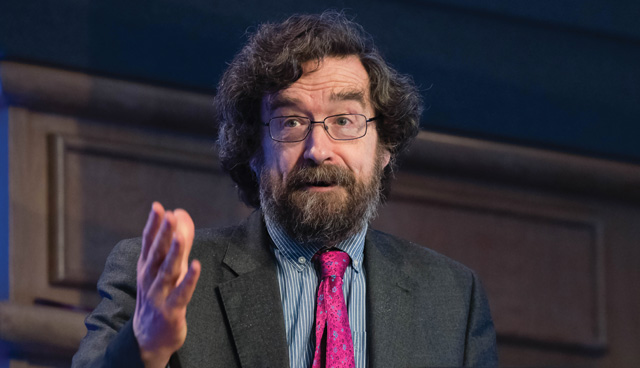

John FitzGerald, Chairman of the National Expert Advisory Council on Climate Change provides an analysis of Ireland’s energy policy and how the country must drastically change direction in order to meet its Paris objectives.

“There are only two ways of dealing with climate change,” says John FitzGerald. “We can go back to living in the way that our grandparents and great grandparents lived, which we all know isn’t politically acceptable. The alternative is using technology,” he continues. FitzGerald outlines the ultimatum given to the Irish Government, which comes amidst a period of environmental failure from authorities and key decision makers. “If you’re worried about climate change like I am, then you will be concerned to hear that in Ireland, things are getting much, much worse.”

According to FitzGerald, figures released by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) make for a sobering read. Projections for greenhouse emissions, released in May, demonstrate that Ireland’s current renewable energy policy is sending the country in the wrong direction. “Depressingly, EPA statistics show that for the very first time, climate policies in Ireland have made things worse, as opposed to improving the situation,” explains FitzGerald. “Although the figures are, to an extent, archaic because of its exclusion of the National Development Plan, the findings are striking. The problem is that we don’t have a clear, cohesive pathway towards where we need to be – a decarbonised economy and society by the year 2050.”

It is this lack of a pathway, according to the climate change expert, which presents a cause for concern. Indeed, FitzGerald argues that Ireland lags far behind its counterparts, such as the UK and Denmark, who have drawn up achievable objectives regarding meeting the commitments outlined at the 2015 Paris Conference. “My colleagues and I have made strong efforts to persuade the Department to carry out this critically important work. Once this essential work has been completed, we may then look towards a variety of energy policies which may work out for Ireland in the most cost-effective way possible.”

The policies which Ireland currently has in place, however, are contributing to the exact opposite effect of what was intended. Indeed, data from the EPA demonstrates that even with additional measures in place (i.e. policies that were introduced last year), Ireland’s carbon dioxide emissions are continuing to rise at an alarming rate. “We are rapidly approaching a dire situation in Ireland, and unfortunately the authorities do not yet have a policy structure in place which can even begin to address this very serious problem,” explains FitzGerald. “The longer we delay dealing with this problem, the larger this problem becomes – and it is a problem faced by us all,” he adds.

Indeed, the task Ireland is facing should not be underestimated. “If we really began serious work today, we would still have to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by over 0.8 million tonnes a year if we are to come close to achieving our 2050 target,” warns FitzGerald. Whilst reducing emissions is a costly process, it will be the next generation and the generation after that will have to carry the burden of the cost, he argues.

It is the decision to continue with the subsidisation of peat-fired electricity generation which has led to such alarming statistics, contends FitzGerald. “The fact is, if this decision hadn’t been made then peat-fired electricity generation would have been closed by now. However, the current subsidy given to that sector exists to keep them emitting,” he criticises. “That subsidy, aimed at protecting jobs, has amounted to over €100 million in a year. When we take account of the amount of jobs currently in this sector, that means that there is a subsidy of roughly €100,000 or more per person. This is bad news for Ireland,” he continues.

“People are going to have to spend the money themselves, and they won’t do this unless it at least saves them money in the long term. If the price of carbon is high enough, they simply won’t invest in it.”

FitzGerald also raises questions over Ireland’s current usage of biomass as a means of generating electricity. “Even with biomass, it will still emit far more carbon dioxide than coal, and certainly more than renewables. The biomass which would be burnt is cheap biomass that should really be used to meet our renewable heat objective,” he outlines. “Because it’s all going on peat, and because peat has considerable emissions, we will be very unlikely to meet our 2050 objectives. So, this is a lose-lose-lose situation for Ireland,” he adds.

It is not a lack of bright ideas, but a lack of ways to implement them. This, according to FitzGerald, is because Ireland has a habit of failing to learn from its climate policy mistakes. “If we are to succeed, we need an effective price signal and it should be for what we expect over the coming decade. These signals are needed to incentivise and guide us in what we need to do,” he says. “The carbon tax is essential – but the Government gets the revenue, and research shows that if you use that money to cut income tax, the economy will grow more rapidly, as opposed to less rapidly. It’s a win-win situation.”

The most challenging part of Ireland’s climate journey is winning over the hearts and minds of both ordinary people and societal leaders, explains FitzGerald. People must be given a strong incentive to change direction away from the burning of fossil fuels. “Households need to invest 50 billion by 2050 in terms of eliminating emissions from homes. That’s 25 per cent of national income, and the bulk of that burden will, of course, be carried by the taxpayer,” he says. “People are going to have to spend the money themselves, and they won’t do this unless it at least saves them money in the long term. If the price of carbon is high enough, they simply won’t invest in it!”

FitzGerald indicates several ways in which Ireland can seek to deal with this problem. “Our belief is that the carbon tax must be raised in the next budget and must continue to rise until the end of the next decade. This isn’t just an issue for the Government to consider, it’s an issue for the Oireachtas. Unless they are prepared to support the Government in acting – and the Minister indicated he is open to it – we will not tackle climate change. The alternative is introducing a carbon price for the electricity sectors, which is what our British and Dutch counterparts have done. Whether its through regulatory action or carbon pricing, hopefully we can turn a corner for future generations in Ireland,” concludes FitzGerald.

“How are we going to get out of this mess?” he asks rhetorically. “We are lost without a map. Telling the people of Ireland that they must conserve energy without letting them know how will change nothing.”