The worrying rise of the precariat

Low paid, low hour jobs are damaging Ireland’s society warns Macdara Doyle.

An expert group from the University of Limerick has uncovered significant problems with low hour, insecure and precarious work in Ireland.* The study arose directly from repeated trade union insistence that precarious work was an issue of growing concern and one which required an official response.

More specifically it arose from the problems brought into the daylight by the 24 hour stoppage in Dunnes Stores earlier this year, where ‘management’ of peoples working hours made normal life an impossibility.

Leaving it to the market is not an option, particularly as this new form of insecurity is precisely what the market has wrought, over recent years. It is a natural outcome of the more aggressive strain of free market neoliberalism that plunged the developed world into crisis in 2008 and, as yet, shows no sign of abating or weakening.

This growth of insecure work has been in abundant evidence across the developed world for some time, so there was no reason to suspect that Ireland might somehow be an exception and buck the global trend. Equally, the 2008 crash here presented fertile ground for such growth, with high unemployment and downward pressure on wages and living standards.

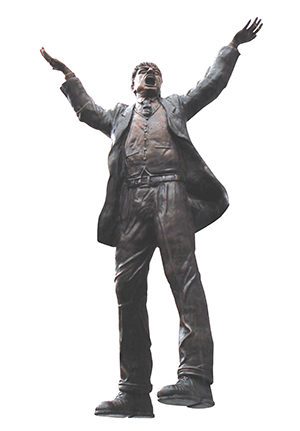

It has created a new social class – the precariat. The term was coined by Professor Guy Standing of the University of London, who has written extensively on the subject.

Standing defines the precariat as consisting not just of everybody in insecure jobs but those who feel their lives and identities are made up of disjointed bits, in which they cannot construct a desirable narrative or build a career. Standing believes that because of flexible labour markets, the precariat cannot draw on a social memory, a feeling of belonging to a community of pride, status, ethics and solidarity.

The University of Limerick was, in key respects, the first official recognition of the existence of a new precarious workforce in Ireland and that in part explains its significance. But almost as soon as the UL report made it into the public arena, it was the subject of wilful misrepresentation.

Employer groups immediately attempted to portray its findings as a thorough vindication of their position: no zero hour contracts in Ireland, nothing to see here. It was a somewhat dishonest attempt to obscure a reality that is far more troubling than it may at first appear.

Anyone familiar with the issue will know that, unlike the UK for example, ‘zero hour contracts’ have been effectively outlawed here since 1997. Thus, an effective minimum threshold of 15 hours weekly was set by 1997 Organisation of Working Time Act.

Indeed, it was the Nevin Institute which recently pointed to the spread of precarious work into wider sectors of the economy, saying it impacted “not only on young people, women and migrants but on older workers too and not always in the more traditional areas of construction, retail, hotels and restaurants.”

And the UL study has confirmed this observation, pointing to the phenomenon of ‘If and when’ contracts and outlining their prevalence across key areas of the economy, from accommodation to food and retail and key areas of the health and education sectors.

Low hour, low pay, insecure and precarious work benefits no one but bad employers, whose parsimony is subsidised by the social welfare system. Long-term, it damages economic growth and has a corrosive impact on equality. Having acknowledged the problem and uncovered the evidence it is now in the government’s best interest to remedy it.