TRADE UNION DESK: Has the long weekend had its day? Irish public holiday questions answered

Are public holidays outdated, or do we get too few? Do you lose out if they fall on days that you are not rostered to work, and how much is the new one – for St Brigid’s Day – costing businesses? The Irish Congress of Trade Unions’ (ICTU’s) Laura Bambrick answers some commonly asked questions about these extra days off work.

Whether you call it a bank holiday, public holiday, or long weekend, if you are an employee, you are likely to be counting down the weeks to the next one, when most businesses will close, and we get to enjoy a paid day off work.

When are they?

We have 10 public holidays each year: New Year’s Day, St Patrick’s Day, Easter Monday, the first Monday in February, May, June and August, the last Monday in October, Christmas Day, and St Stephen’s Day.

In years where St Brigid’s Day, or 1 February, falls on a Friday, the Friday will be the public holiday instead of the first Monday. This will first occur in 2030.

Good Friday is not a public holiday. It is a bank holiday – banks close on the day. Other workplaces choose to take Good Friday off, but it is not an official holiday covered by legislation. It is in Britain and Northern Ireland. For the rest of us, it is a normal working day.

Do some employees miss out?

To ensure that all employees get the benefit of a public holiday, if you are required to work on the day one falls your employer must instead give you a different day off within a month, or add an extra day to your annual leave, or pay you one day’s pay in lieu. Your employer gets to decide which option will apply to you.

Part-time employees also qualify, but you must have worked at least 40 hours in total in the five weeks prior to the public holiday. There is no 40-hour service requirement for full-time employees, it is a day-one right. Part-timers who do not normally work the day the holiday falls on, are entitled to be paid one-fifth of their weekly pay.

How much do they cost business?

The St Brigid’s Day holiday was introduced by the last (34th) government as part of a package of new employment rights to thank workers for getting the State through the Covid-19 pandemic. Introducing a new public holiday was not without its critics among employers, who were ostensibly concerned about the increased labour costs for their business. In fact, one Kerry hotelier went so far as to claim “no one wanted” the new one. Some 2.5 million employees beg to differ.

But public holidays do come at a cost. In 2024, the Department of Enterprise, Trade and Employment published a hefty 175-page impact assessment of improvements to workers’ rights. It estimated the cost of an extra public holiday for the economy was 0.09 per cent of GVA in 2023, equating to €355 million.

However, the cost of a public holiday is not evenly spread across the economy. Some sectors, such as tourism, hospitality, recreation and retail, are impacted disproportionately because of the wage costs for staff who work on the day, as we ell as the relatively high share of part-time employees, who are entitled to compensation. On the other hand, people spend more money on public holidays and these sectors benefit most from a boost in consumer spending.

Does Ireland have too few?

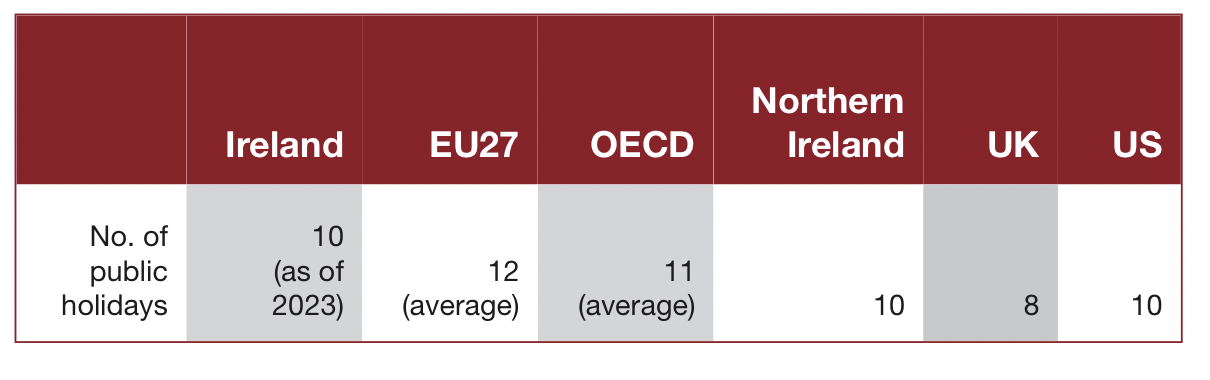

The new St Brigid’s weekend brings the total number of public holidays to 10 each calendar year, putting us on an equal footing with Northern Ireland but still lagging behind the EU average of 12 per annum.

This does not necessarily mean Irish workers are getting short-changed. In many European countries, certain public holidays are not automatically replaced if they fall on a Saturday or a Sunday. Unless time off in lieu of public holidays falling on a weekend is covered by an agreement between trade unions and employers, employees in those countries may have fewer days off work in some years than in others.

In Ireland, when a public holiday falls on a weekend the law entitles employees to a substitute day off, with most businesses opting to remain closed on the following Monday. This guarantees all Irish employees the benefit of 10 public holidays every year.

Are they outdated?

Public holidays first became law in 1871, at a time when the working day and week were considerably longer than legally permitted today. The workforce is also much more diverse now, with fewer of us sharing a cultural or religious attachment to these set days.

However, it would be a very brave decision by any government to take away workers’ holiday time. But it has happened, with predicable backlash.

In 2005 France scrapped one of its 11 public holidays. Not only did French employees lose their right to a paid day off but they were to work the extra day without pay – their wages instead going into a government fund for improving eldercare. Employers and the self-employed were exempt from this 100 per cent income tax ‘day of solidarity’. After three years of anger and resistance from PAYE workers and their unions, the public holiday was restored.

In Ireland today, low-paid workers do not generally get more than the legal minimum annual leave required of their employer – 20 days for a full-time employee, which has remained unchanged for nearly 30 years. Public holidays bump up the minimum time off work to 30 days. So, while public holidays began in the 19th century to give workers a well-deserved break, far from being a relic of our past, they are still fulfilling this vital function.