TRADES UNION desk

Strip away the glitter and the sleek PR and it quickly becomes apparent that there is something fundamentally Dickensian about the much-vaunted ‘gig economy’. ICTU’s Macdara Doyle writes.

In fact, as it relates to the world of work – and therefore to people’s livelihoods – this growing component of the global economy functions in an essentially regressive manner, operating as if almost two centuries of social progress never actually happened.

Although proclaimed as a great liberator that would unshackle productive workers from desks and production lines, in reality, its greatest contribution to the world of productive work to date has been to unshackle employers from a whole battery of obligations and responsibilities, that were built up over generations.

Instead, we now see growing numbers of workers shackled to a world of work characterised by insecurity, uncertainty and levels of pay that are often just above the minimum wage.

Basic workplace rights that we often take for granted – decent pay and certainty about hours of work, paid sick leave, paid holiday leave, health and safety provision, pension entitlements – are now alien concepts to many younger workers and those who try to make a living in the gig economy.

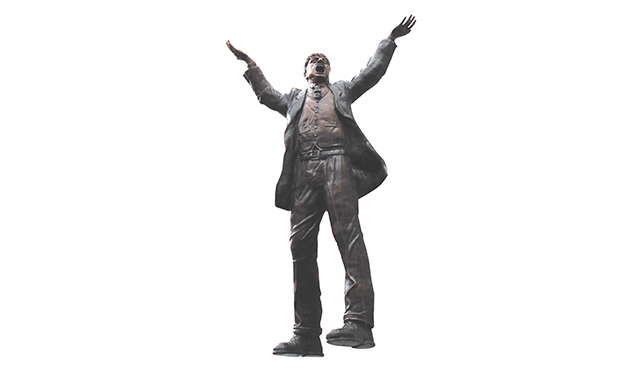

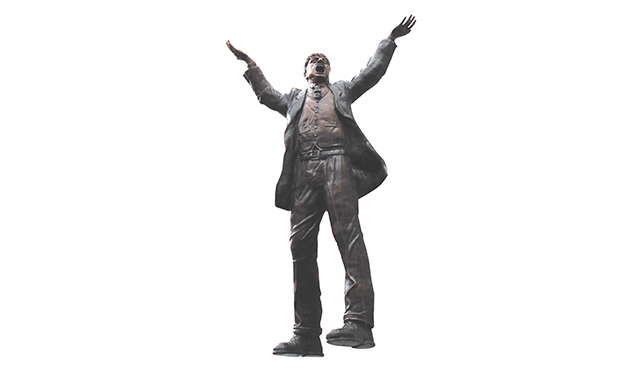

The company names may be new, but the principles that underpin many of their operations are but a replica of the system of casual labour that obtained on Dublin’s docks in the 1900s and in the hiring fairs of the same era. The examples are legion.

Workers at Amazon – a multibillion dollar corporation – reduced to living on food stamps in the US, because of poverty wages1 or collapsing at work due to exhaustion and impossible management targets.2

Uber drivers earning wages that sit just above the poverty line.3 A courier for DPD in the UK who was fined for taking a day off work to see a doctor, who worked on through illness, before he collapsed and died.4

Or a the Deliveroo boss who warned UK legislators that paying ‘their workers’ decent rates would essentially make the business untenable.5

Ironically, unbeknownst to himself, he was putting forward the same essential arguments that were once deployed in defence of slavery or utilised by factory bosses in Industrial Revolution Britain, speaking up for their right to send young children down mines or to work (and die) in large mills.

But perhaps the biggest challenge presented by this supposedly new economy is the fact that, ultimately, it is self-defeating. Low paid and insecure workers produce little and buy less. The more who are employed in this manner, the less secure capitalism itself becomes. This essential truth was understood by a previous generation of industrial magnates and was reflected in Henry Ford’s decision to pay double the going daily rate to his workers.

It also played a role in the ‘creation’ of the US middle class in the 1940s and 1950s, although the main driver of this era of relative prosperity and job security was the trade union movement, strong enough to provide an effective counterweight to capital and a vehicle for wealth redistribution. The global decline in union strength correlates directly with the falling share of wealth that goes to workers and an inevitable rise in societal inequality.

The problem with the labour force is that you cannot throw a quarantine around one sector and insist it will have no wider impact. Just as water finds its own level, so too the low standards that prevail generally in the gig economy will seep into the wider economy and help to drive down standards across the board.

Insecure and precarious work is now a worrying feature across many sectors, from healthcare and education to retail and media. For change to be effective it will need to happen at a European and global level.

To date, national governments and European institutions have appeared either paralysed by indecision or in thrall to the global giants that are reshaping economies and the world of work to suit their own needs. But that is slowly changing and pressure is growing from within Europe to draft EU wide legislation that would enforce workers’ rights and begin to impose minimum standards across the sector.

Not before time.

Read the Congress report on the growth of precarious work. Click here

1. www.newsweek.com/jeff-bezos-amazon-employees-food-stamps-782714

2. www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/amazon-workers-working-hours-weeks-conditions-targets-online-shopping-delivery-a8079111.html

3. www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2018-03-08/uber-drivers-earn-pay-that-s-just-above-the-poverty-line

4. www.theguardian.com/business/2018/feb/05/courier-who-was-fined-for-day-off-to-see-doctor-dies-from-diabetes