Transport innovation for sustainable development: a gender perspective

Rachel Cahill, Head of Executive Office and Sustainability Lead, Transport Infrastructure Ireland writes of how everyday stories inspire new thinking and how Transport Infrastructure Ireland gained a deeper understanding of the transport experience for women.

The climate crisis poses an urgent need for a fundamental reimagining of how we live and how we move.

According to the International Transport Forum (ITF), “climate change cannot be stopped without decarbonising transport”. Achieving this is one of the most urgent and complicated challenges facing the global transport sector.

In contrast with other sectors of the economy, transport has yet to succeed in significantly reducing its carbon intensity. Without more effective and transformative measures to decarbonise transport, it appears that Ireland will struggle to meet national emissions targets, even with substantial progress in other sectors.

As the national body charged with delivering safe and efficient transport infrastructure and services, Transport Infrastructure Ireland (TII) is stepping up and advancing its agenda on climate action and decarbonisation in line with the Government’s Climate Action Plan and the Programme for Government.

Key aspects include major new infrastructure and service delivery projects such as the new Luas system in Cork and MetroLink in Dublin (in partnership with the National Transport Authority), in addition to demand management strategies to facilitate modal shift and a transition from private, low occupancy transport, such as cars, to public transport modes.

As 2021 begins, it is obvious that transport is being repositioned. Despite the recent arrival of viable vaccines against Covid-19, any ‘return to normal’ for the foreseeable future will involve more working from home, more time spent locally, less socialising outside the household and fewer long trips for work and leisure.

We must continue to deliver safe, efficient, and decarbonised mobility solutions to enable long-term well-being and prosperity. Never has there been such a need to rapidly address and promote sustainable and active modes of transport such as walking and cycling.

So, how do we bridge the gap between high-level aspiration and bringing about real change? One area to focus on is gaining a deeper understanding of travel behaviour and the factors that contribute to people’s decisions around choosing their primary mode of transport.

Research from the ITF tells us that gender is one of the biggest determinants when it comes to travel behaviour and transport options. At a time when influencing the modal shift is of critical importance, understanding the role of gender in transport and the travel patterns and needs of 50 per cent of the population is an obvious starting point.

In this context, TII has taken up the challenge of studying and understanding women’s mobility in its new study Travelling in a Woman’s Shoes (July 2020). The research seeks to understand the realities for women in Ireland today: why they make the mobility choices they do, what are their daily challenges and aspirations.

Filling this gender data gap is the first step in balancing male bias in the design of future transport solutions.

Decarbonising transport should not be considered simply as a technical or an engineering challenge; it is also a social and cultural challenge.

Nor should it be considered in isolation from the need to develop our economy and the transport industry in line with UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Tackling climate change and decarbonising transport is part of a broader need to transform the transport sector to become a much more sustainable sector (which the World Bank defines as a safer, greener, accessible, and more efficient sector). Yet experience shows that delivering this vision of a sustainable transport sector is challenging and not so easy to achieve.

Therefore, this is a huge opportunity for the Irish transport sector to come together and work collaboratively with our partners, stakeholders, and communities so that the findings from this report can influence modal shift and inform future policy and decision making, making sustainable transport options feel safer, more attractive, and more accessible to everyone.

The challenge

Transport is often seen as gender-neutral, providing benefit to all equally. However, a growing body of international research highlights that this is not the case, including work carried out by the United Nations Commission (2014) on the Status of Women which found a male bias in the planning, provision, and design of transport systems.

Women and men can have different needs, constraints, and expectations for using transport. If women feel more empowered and find it safe to use sustainable transport modes such as walking, cycling, public transport and carpooling, there will be less dependence on cars, more public transport trips taken across the day and night, and enhanced quality of life for all.

At the same time, the planning and design of a safe, reliable, and equitable transport system will also encourage men to become less car dependant and give them more sustainable transport mode choices as part of their daily routine.

Travelling in a woman’s shoes

TII’s study, which investigates the needs and travel behaviours of women, is a first of its kind in Ireland, and we are delighted to be part of an essential step towards a deeper understanding of the transport experience for women.

Across the world, men and women have different travel needs for two main reasons.

First, mobility is heavily shaped by gender roles performed by women and men. Women still undertake a substantial portion of household and care-related activities daily which, when combined with work and education, make their travel patterns more complex. When you compare this with a commute to work in a business district, this mobility is often characterised by multi-purpose travel and ‘trip chaining’.

Second, women’s mobility is more likely impacted by unsafe experiences and concerns for personal safety. As a result, women are exposed to greater levels of ‘travel burden’ than men relating mostly to cost, stress, time poverty, lack of accessibility and, above all, safety. There is growing international research demonstrating that this travel burden results in high car dependency and a cohort of women not leaving the house.

Travelling in a Woman’s Shoes analysed available data and studies from Ireland and relevant global literature. The primary research involved an ethnographic study where we conducted 21 two-hour in-home interviews with women in Dublin and Cork and a statistically significant quantitative survey to validate our findings.

The study tells real-life stories that demonstrate the key characteristics of women’s mobility in Ireland. A research method which is not typically used in transport research, this ethnographic approach adds another dimension to existing transport research.

The study shows us how issues of gender equality and social inclusion are well suited to the ethnographic method. This allows us to shed light on the disparities and the realities that women face every day, introducing a diversity of perspectives and enriched data that applies a gender lens to travel behaviour.

Understanding gender issues in transport

Research participants were selected to represent a diverse demographic and geographic background, including varied daily transportation usage and behaviours. As part of the fieldwork, we also accompanied women on aspects of their everyday journeys to observe how they interact with the existing transport infrastructure.

Insights into the role of this ethnographic method in shaping future sustainable transport policy and planning are outlined below:

- Ethnographic research produces evocative and nuanced insights into people’s lives and the role of mobility. It leverages the power of a person’s own words to create a vivid impression of an issue or concern faced by a woman on her journey.

It is an essential vehicle for communicating complex problems and may be more effective in motivating the transport sector to engage in the subject than high-level statistical data. - An ethnographic approach enables sensitive and complex human issues to be tabled and socialised in a government and business transport context. Through people candidly telling their stories, a broad range of social, infrastructure and technological issues are revealed without polemic. The integrated nature of mobility and socio-economic issues is made clear.

- The study was able to capture feelings of fear, stress, and joy, which are significant motivators of transport behaviour, but which are often left out of customer surveys.

- This method provides a window into what is happening beyond existing measures, key performance indicators and statistical data. Decision-makers can observe the impact of transport and land use policies in real contexts.

- Photos taken from women’s journeys are an essential part of the storytelling process.

- Women’s rich and detailed anecdotes about their everyday mobility hold the clues to sustainable solutions. Transport innovation – technological, engineering-based, and social – need to start from these stories.

This type of research is highly suited to understanding gender issues in transport. It can enable the transport sector to understand the complexity and significance of women’s mobility challenges and to innovate on an experiential level. It is an essential tool in designing effective, sustainable solutions.

The findings of this research study show us that understanding modal shift, decarbonisation and a smaller scale post-pandemic travel landscape is about understanding everyday life.

It shows us that, when designing and integrating mobility solutions and land use policy, we need to consider that people are situated with families, gendered roles and work, fears, mental maps, joy, and risk appetites. Delivering sustainable mobility in the future is about unpacking these situations.

A better understanding of the everyday stories of women takes us beyond high-level statements about inclusion by introducing voices that are often absent from formal consultation processes.

These generated rich and unexpected insights about the barriers, challenges and mental models driving mobility choice, specific to the Irish context. We used a robust, nationally representative survey of more than 1,000 respondents (male and female) to validate the hypotheses generated from the literature review and ethnographic research.

What we found

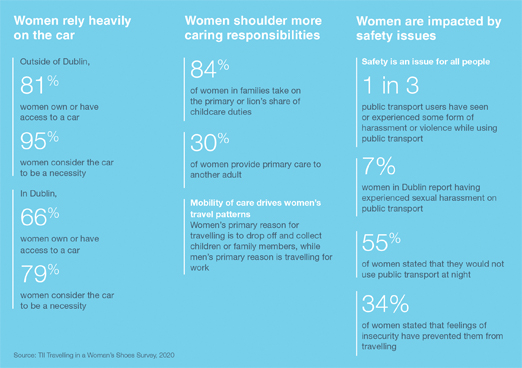

What drives women to choose their primary transportation methods? We found that transport habits are socialised from an early age. For some, learning to drive and getting a car is a coming-of-age moment while for others, using public transport allows women to be independent from caregivers. Several women we spoke to talked about the freedom public transport gave them.

However, when life becomes more complex, women typically become more time poor, balancing job requirements and household tasks with the arrival of children. Public transport no longer becomes a viable option for complex trip-chaining and is not seen as being child friendly.

Even for many women who use public transportation to commute, having a car remains a ‘necessity’ for chores and other spontaneous emergencies, given how unreliable public transportation can be.

When it comes to different mobility options, women consider the car to be the most pleasant and least stressful mode of transport, in comparison to the bus, for example. The car can also be associated with empowerment and joy.

However, over time, for many who drive every day, it can become stressful, tedious, like a burden chore – especially given traffic congestion and for women with young children who do not feel confident driving.

For women, the key issues with public transport include indirect routes and long wait times, lack of reliability, lack of support for care-giving needs and a lack of feeling safe.

Socio-economic and geographic factors also influence women’s mobility experience. Across regions, cities, and neighbourhoods, women have different relationships with mobility and public transportation.

In many rural areas, public transport is not available; as such growing up, women do not have the opportunity to learn how to navigate a public transport system. They may experience different forms of freedom and independence but are less experienced with public transport, density, anti-social behaviour etc. – which can be challenging when moving to a city for school/jobs.

Overall, we found that Irish women’s mobility is hindered by existing household gender dynamics that place the burden on them.

Women are also adversely impacted by being and feeling unsafe in public, particularly when walking and using public transport.

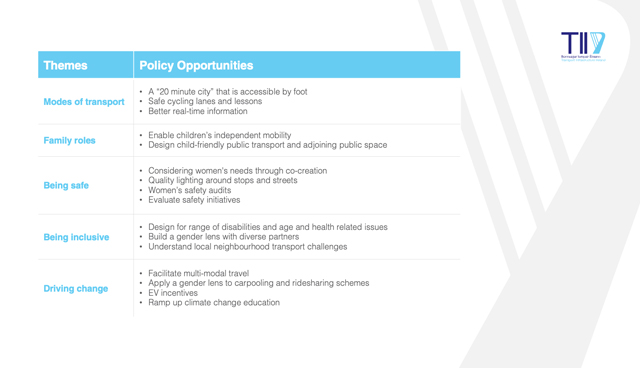

The real-life stories of women allowed us to explore additional central themes which influence mobility: that is, how family, safety, and diversity shape transport choices. The table below illustrates some of the policy opportunities in response to these themes.

Rachel Cahill

Head of Executive Office and Sustainability Lead

rachel.cahill@tii.ie