UK legacy legislation: Ireland pursues legal avenue

Ireland has initiated its first interstate case against the British Government at the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) since the ‘hooded men’ torture case in 1971.

In December 2023, Taoiseach Leo Varadkar TD announced that his Government would pursue a legal challenge against British Government legislation relating to ‘Troubles’ legacy under the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR).

Indicating that all political options had been exhausted and expressing regret that “such a choice had to be made”, Tánaiste Micheál Martin TD asserted: “The decision by the British Government not to proceed with the 2014 Stormont House Agreement and instead pursue legislation unilaterally, without effective engagement with the legitimate concerns that we, and many others, raised left us with few options. The British Government removed the political option and has left us only this legal avenue.

“The incorporation of the European Convention on Human Rights into Northern Ireland law is a specific and fundamental requirement of the Good Friday Agreement. Since the UK legislation was first tabled, the Government have been consistent that it is not compatible with the Convention.”

Following the unilateral pursuit and enactment of the Northern Ireland Troubles (Legacy and Reconciliation) Act 2023 in September 2023, the Irish Government has decided to challenge the British Government in the European Court of Human Rights.

Commonly referred to as the Legacy Act, the legislation is ostensibly intended to “address the legacy of the Northern Ireland Troubles and promote reconciliation” by:

- creating an Independent Commission for Reconciliation and Information Recovery;

- limiting criminal investigations, legal proceedings, inquests, and police complaints;

- extending the prisoner release scheme in the Northern Ireland (Sentences) Act 1998; and

- providing for “experiences to be recorded and preserved and for events to be studied and memorialised, and to provide for the validity of interim custody orders”.

However, the Act has succeeded in unifying victims’ groups and political parties of all shades in their opposition to it. Indeed, the Government has noted the “near universal opposition to the Legacy Act on the island of Ireland”.

To date, in spite of five multilateral agreements – from the Good Friday Agreement 1998 to New Decade New Approach 2020 – consensus on the investigation of unsolved serious crimes during the ‘Troubles’ has not been reached. Disparate inquests, investigations, and civil litigations have filled the vacuum.

Speaking in Dublin in December 2023, Varadkar insisted: “We would prefer not to be in this position. But we did make a commitment to survivors in Northern Ireland and to the families and victims, that we would stand by them. respect their wishes, and also stand by the Good Friday agreements, which specifically references the European Convention of Human Rights… we really have no option but to ask the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg to carry out a judicial review of this legislation.”

Before the legislation’s enactment, and following a visit to the UK in June 2022, the Council of Europe suggested that the UK Government should “consider withdrawing the Legacy Bill in view of the widespread opposition in Northern Ireland and the serious issues of compliance with the European Convention on Human Rights it raises”.

In her December 2022 report, Commissioner for Human Rights, Dunja Mijatović observed: “Any further steps on legacy must place the rights and needs of victims at its heart.” That same month, the Council of Europe Committee of Ministers also “strongly reiterated” calls for the legislation to be amended “to allay… concerns about compatibility with the European Convention”.

In January 2023, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Türk echoed Mijatović’s observations and indicated: “Respect for rights of victims, survivors, and their families to truth, justice, reparation and guarantees of non-recurrence is essential for reconciliation. Their rights must be placed at the heart of all attempts to address the legacy of the ‘Troubles’.”

Urging the UK Government to “engage in further meaningful and inclusive consultations” to address the ‘Troubles’ legacy, he noted that the draft legislation – which was subsequently enacted – “appears to be incompatible with the UK’s international human rights obligations”.

“Introducing conditional immunity in this manner would likely be at variance with the UK’s obligations under international human rights law to investigate and, where appropriate, prosecute and punish those found responsible for serious human rights violations…

“Concerns remain that the Bill would obstruct the rights of victims, survivors and their families to effective judicial remedy and reparations, including by prohibiting most criminal prosecutions and civil actions for ‘Troubles’-related offences,” he said.

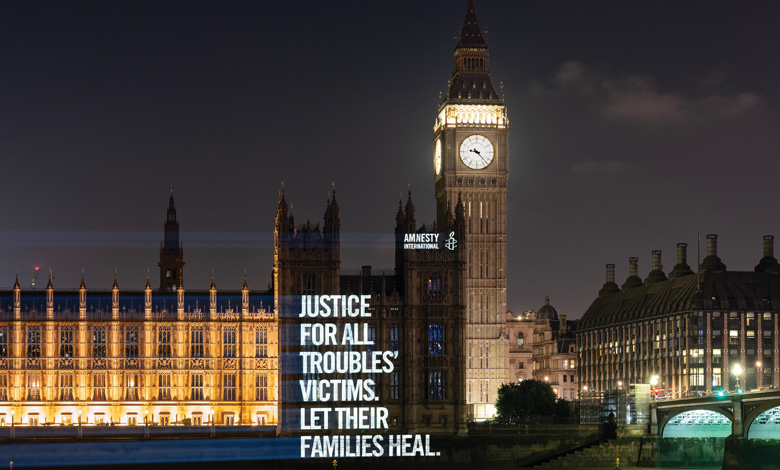

Welcoming the “state-level” legal challenge, Amnesty International’s Gráinne Teggart asserted: “The Irish Government is doing the right thing for victims, for the rule of law, and for the upholding of human rights. Victims’ rights to truth, reparations, and justice must be realised. This challenge is vital for victims here and around the world, who face the prospect of similar state-gifted impunity.

“The UK Government doggedly pursued this legislation which shields perpetrators of serious human rights violations from being held accountable. It is important that the Irish Government takes this stand… We hope this critical litigation will bring all Troubles victims closer to the justice they deserve.”

Speaking at the International Academy of Trial Lawyers Conference in Killarney, County Kerry in April 2023, the current President of the ECtHR, Síofra O’Leary warned: “Our rulings do not always please, either the respondent governments to which they are addressed, or members of the public,” adding: “As a court of law we are charged with interpreting and applying the law of the Convention whilst often navigating very choppy political waters… politics are never far from our courtroom, but politics is not what we do.”

The Strasbourg Court is, O’Leary suggests: “A judicial canary in Europe’s democratic mine; an early warning signaller which points to where European states are failing with reference to their commitments to democracy, the rule of law and the protection of human rights.”

In January 2024, the ECtHR has now confirmed that it has formally received Ireland’s case in which it contends that provisions of the UK legislation are incompatible with Articles 2 (right to life), 3 (prohibition of torture and inhuman or degrading treatment), 6 (right to a fair trial), 13 (right to an effective remedy), and 14 (prohibition of discrimination) of the ECHR.

However, with both the metaphorical and literal clock ticking for victims and survivors, and a backlog of some 76,000 cases pending according to O’Leary, it remains to be seen whether the legal process against the UK will reach a timely conclusion.